THE TWO MARRIAGES

OF THE VIRGIN

A unique dialogue in the history of art

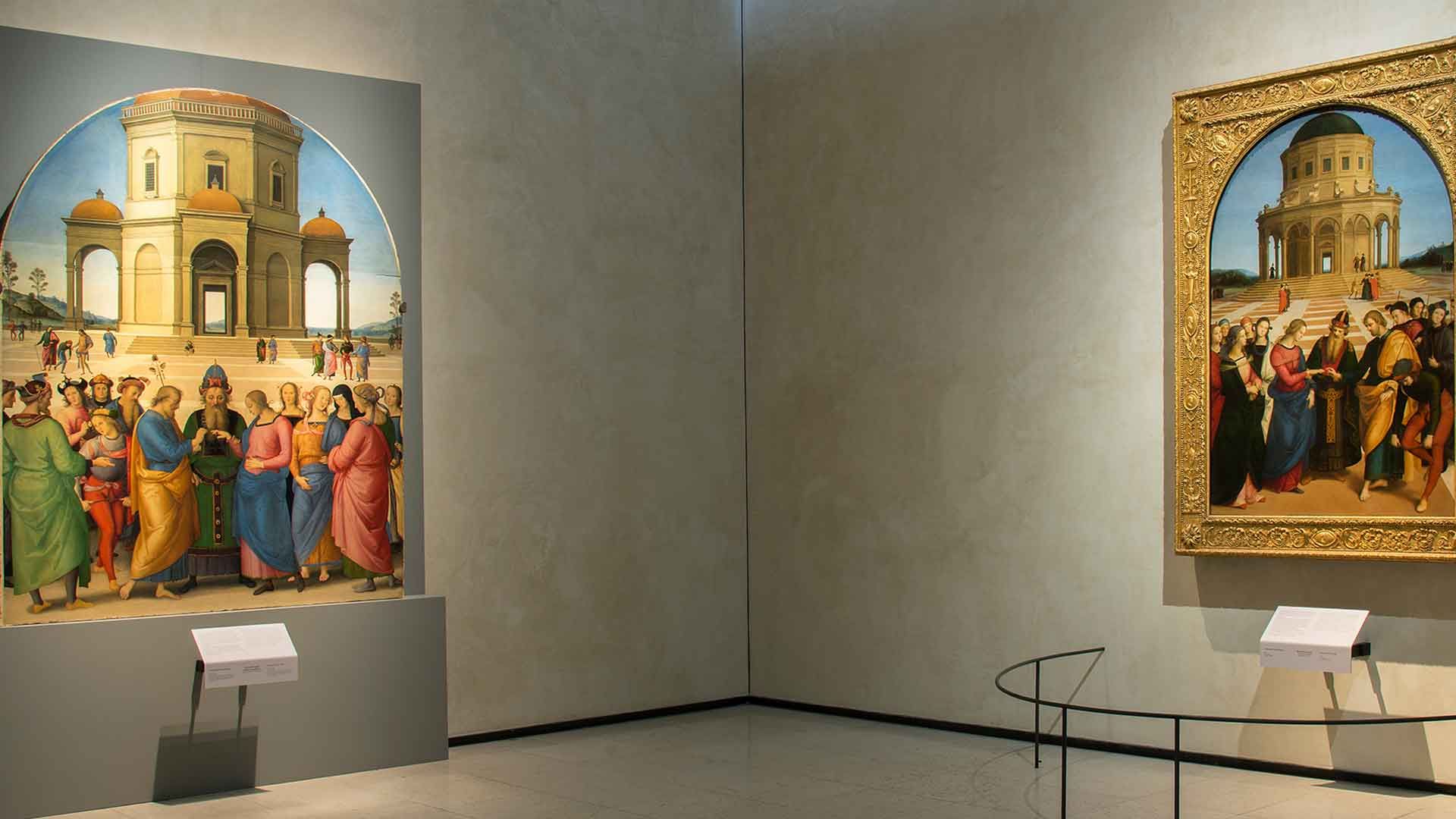

Two crucial works in the history of art came together at the Pinacoteca di Brera in an exceptional encounter in 2016: Raphael’s Marriage of the Virgin, one of the museum’s most iconic works, and Perugino’s Marriage of the Virgin from the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Caen, were displayed side by side for the very first time in Brera.

Depicting the same subject matter and bound to one another in numerous other ways, Perugino’s altarpiece and Raphael’s picture are shown in dialogue in every art history manual, yet they had never “met in the flesh”.

This once-in-a-lifetime event highlighted the dialogue between Perugino, the master, and Raphael, his pupil.

James M. Bradburne presents the first dialogue: Raphael and Perugino, on two Marriages of the Virgin

The Two Marriages

When Pietro Vannucci, known as Perugino, painted his version of The Marriage of the Virgin, he was running one of Italy’s most prestigious workshops.

His reputation rested on the leading role he had played some twenty years earlier in frescoing the middle register of the Sistine Chapel with his uniquely calm and softly monumental style.

The master’s reputation attracted numerous artists to his workshop, including the painter Giovanni Sanzio’s young son Raphael, as Vasari informs us.

So, it is hardly surprising that this young genius, already a successful painter in his own right, should have taken his cue from Perugino’s picture to produce the masterpiece that marked the end of his own formative period, after which he moved to Florence.

Perugino’s altarpiece, commissioned by the Confraternity of St. Joseph for the Chapel of the Sacred Ring in the Cathedral of San Lorenzo in Perugia, was painted between 1499 and 1504 and displayed alongside the relic of the Virgin’s Sacred Ring.

Raphael painted his altarpiece in 1504 for the Chapel of St. Joseph in the church of San Francesco in Città di Castello, a town situated about 70 km from Perugia.

Perugino’s composition is inspired by his famous fresco depicting the Handing Over of the Keys in the Sistine Chapel, reworked to allow for the altarpiece’s vertical format. The setting is once again a square with a circular building in the background and a centred perspective, but the figures in the foreground are more tightly packed.

Though repeating the same composition, Raphael distributes his figures more freely to create greater visual interaction with the building on its raised platform, which becomes the hub of a large and harmonious circular space.

The story of the paintings in dialogue in Brera

This first Brera dialogue allowed visitors to explore the relationship between the master and his pupil at a crucial moment in Raphael’s career just as he was getting set to move to the Florence of the Medici.

The paintings also provided an opportunity to tell a more complex tale, possibly less well-known but emblematic of a typically Italian story combining art, history and municipal rivalry. The astonishing reputation of Perugino’s altarpiece was due from the very outset to the fact that it was to hang on the altar of the Chapel of the Ring in Perugia Cathedral.

THE SACRED RING

The relic is a small chalcedony ring which, tradition claims, the Virgin gave to the Apostle John before she died and which found its way during the Middle Ages to Chiusi, where it was kept first in the church of Santa Mustiola and then in San Francesco.

In 1473, it was stolen by one of the convent’s own friars who gave it to Perugia, triggering a struggle with no holds barred between the two cities.

It took Pope Sixtus IV’s intervention to put an end to all the retaliation and boycotting, with the ring finally being allocated to Perugia.

For several years, the relic was kept in the Cathedral, in the Chapel of the Decemviri of the Palazzo dei Priori, until, in 1488, it was entrusted to the canons of the Company of St. Joseph and placed in the Cathedral’s Chapel of St. Joseph dedicated to the Sacred Ring, where it is still kept today. Perugino’s altarpiece was commissioned for the altar in that chapel.

As so often – for instance with the Sacred Girdle in Prato or the Holy Blood in Mantua – in addition to the relic’s religious and devotional value, it also become a symbol with which the entire city identified, a sentiment bolstered by Perugino’s painting adorning the altar of the marriage par excellence, the inescapable model to emulate.