THE RAPHAEL ROOM AND MORE

The story of the painting’s changing settings

Raphael’s Marriage of the Virgin came to the Pinacoteca di Brera in October 1805, when the Viceroy Eugène de Beauharnais purchased it for the new Pinacoteca on the insistence of the then Director Giuseppe Bossi.

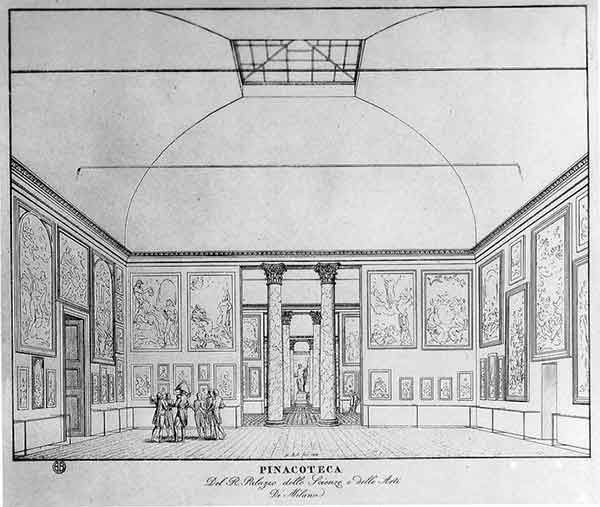

1809

The Marriage was displayed in the rooms obtained by converting the nave of the old Gothic church of Santa Maria di Brera into a modern museum space.

A space in which, under the watchful eye of Canova’s Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker, masterpieces from the regions annexed by the Kingdom of Italy were displayed to serve both for the edification and for enjoyment of the citizens and as models for new generations of artists.

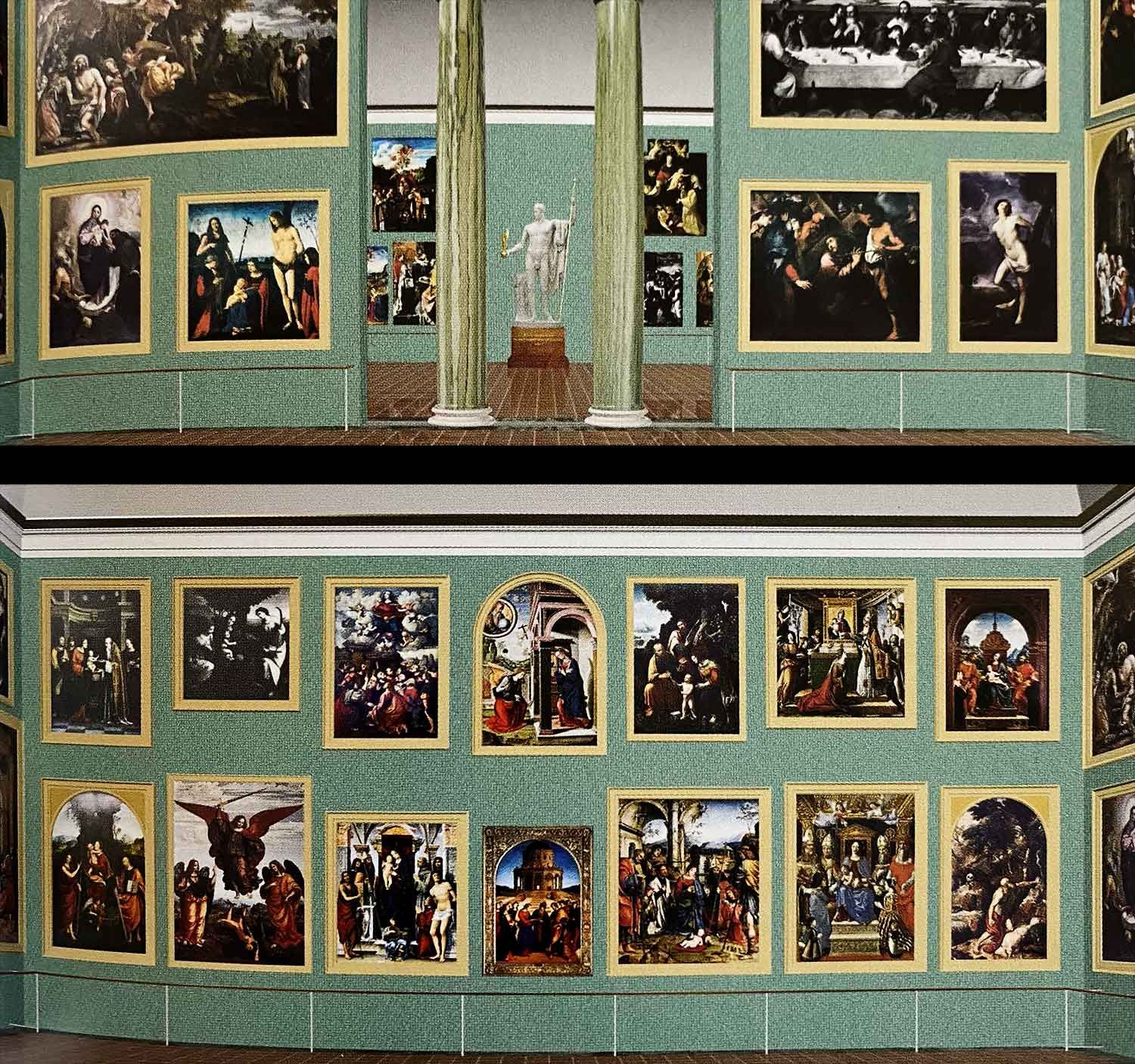

If we reconstruct the layout of the walls using the early guides to the museum, we can see that when it officially opened in 1809, Raphael’s painting was given the place of honour in the centre of the main wall in the room named after him.

In the lower register, the Marriage hung alongside work by other exponents of Renaissance Classicism such as Francesco Francia and beneath an Annunciation from Senigallia painted by Raphael’s father Giovanni Santi.

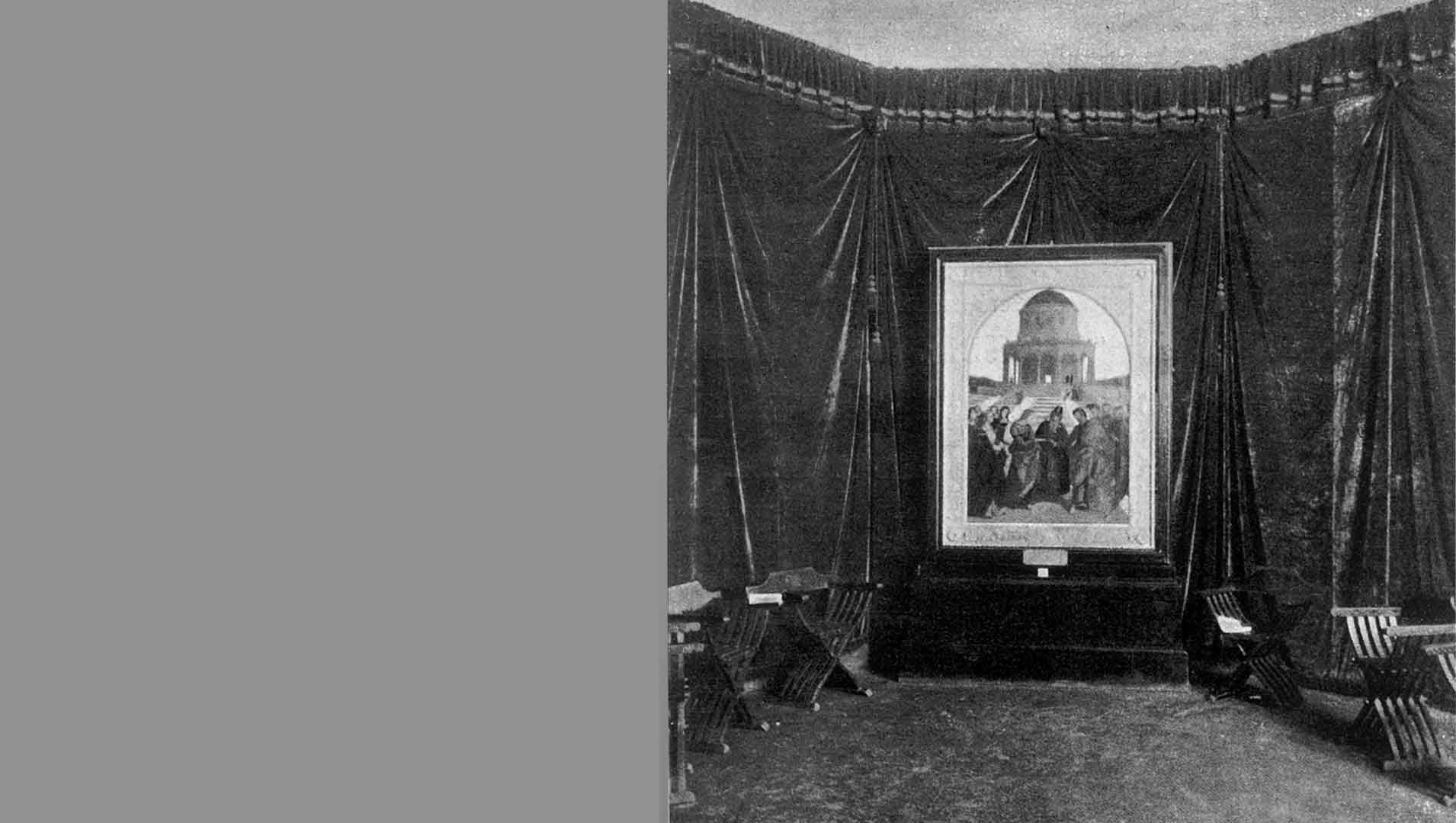

1903

At the turn of the 19th century, Corrado Ricci began to reorganise Brera, rearranging the collections in chronological order and grouping them by regional school, a layout in line with the most up-to-date criteria of his day.

Raphael was naturally included in the Umbrian school, but he had a room dedicated to him and, as the great art historian put it, he was

“alone in the sovereign sweetness of his Marriage of the Virgin”

The painting, set on a base and encased in a glass-fronted showcase, stood against a wall richly draped in green velvet in the room dedicated to Raphael, Room XXII.

While such an arrangement was common for museum walls in the 19th century, the backless, two-armed faldstools, known as Savonarolas, were a tribute to the period when the altarpiece was painted, reflecting the taste for history commonly found in bourgeois homes of the time.

1922

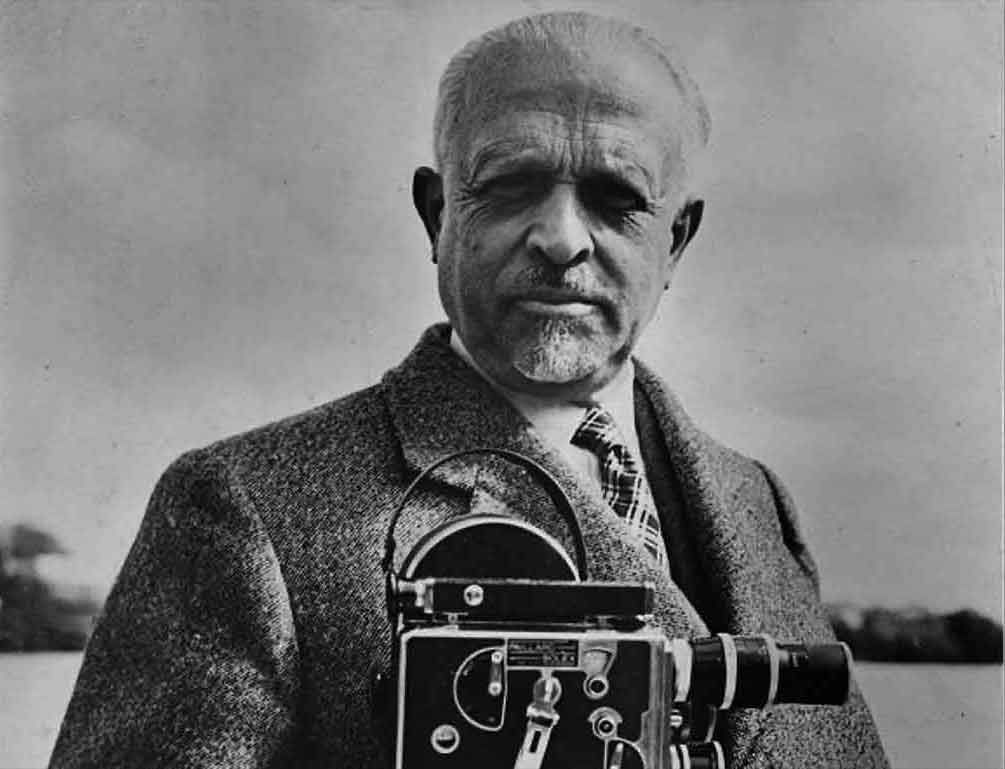

ETTORE MODIGLIANI

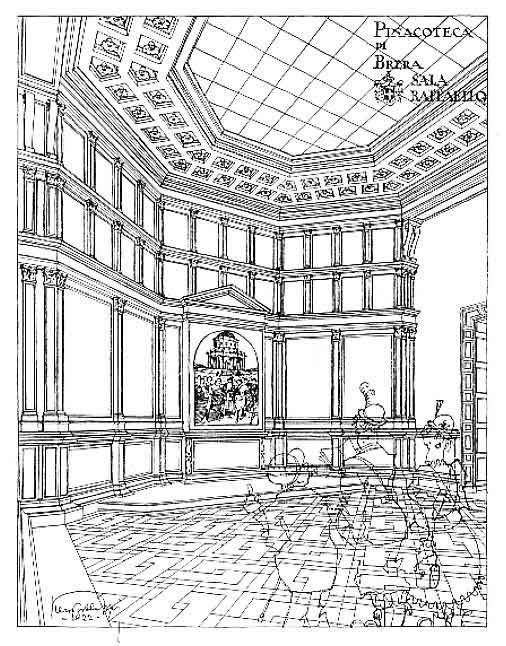

The Raphael Room was renovated under the direction of Ettore Modigliani in 1922 based on a design by Piero Portaluppi, whose new layout revealed something of an ironic vein in its approach to the popularity of Raphael’s iconic altarpiece.

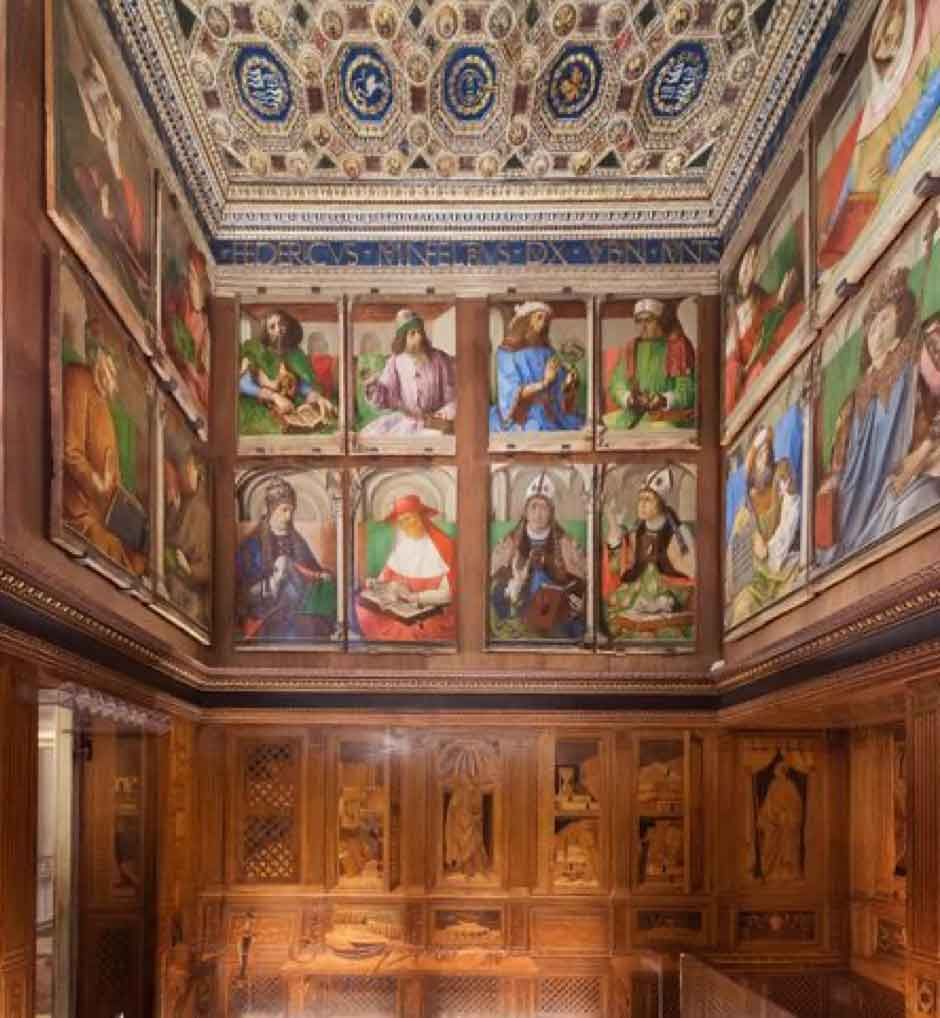

Raphael’s Marriage was placed in a setting designed to conjure up the memory of Urbino, alongside Piero della Francesca’s San Bernardino Altarpiece (still attributed to Fra’ Carnevale at the time) and an early banner by Luca Signorelli.

The layout emulated the studiolo or private cabinet of Federico da Montefeltro, one of the best-known rooms in the Ducal Palace of Urbino, with wooden panelling echoing the studiolo’s inlay and an upper gallery with illustrations of illustrious historical figures.

THE WAR AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF BRERA

During World War II, the altarpiece was evacuated along with many others from the Pinacoteca and taken to Villa Marini Clarelli in Perugia before being moved to the Vatican picture gallery.

Several exhibition spaces in Brera were destroyed during air raids, thus requiring a complete rethink of the collection’s layout at the end of the war.

In the post-war years, Piero Portaluppi had the task to rebuild the Pinacoteca under the watchful eye of Fernanda Wittgens. The Marriage continued to be displayed in tandem with Piero della Francesca, reflecting a critical approach that saw Raphael as the true heir to Piero’s formal and intellectual precepts.

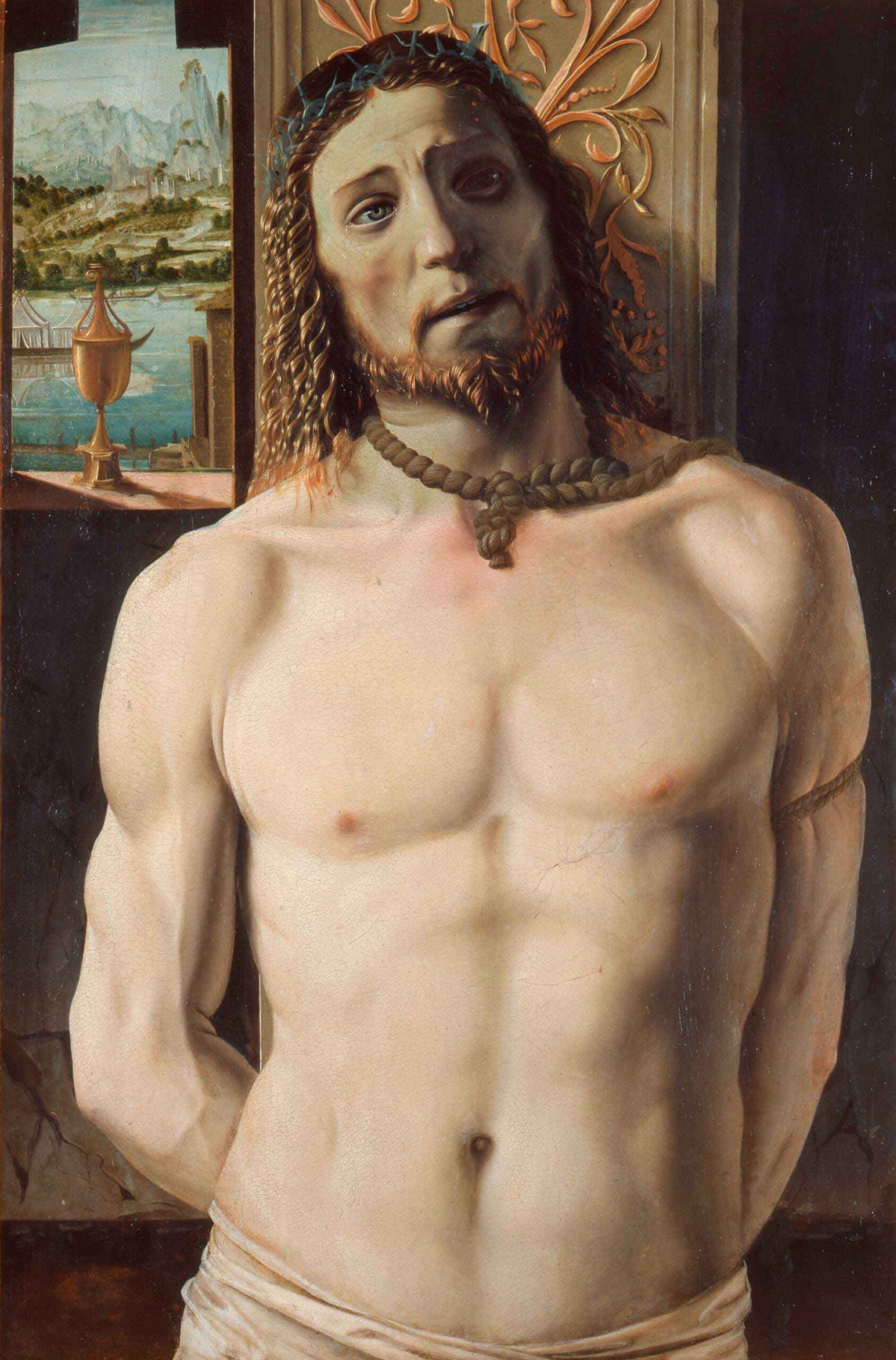

The addition of Bramante’s Christ Tied to the Column, a picture that he had painted in Lombardy, highlighted the themes of perspective and architecture which play a key role in both Raphael’s and Piero’s altarpieces.

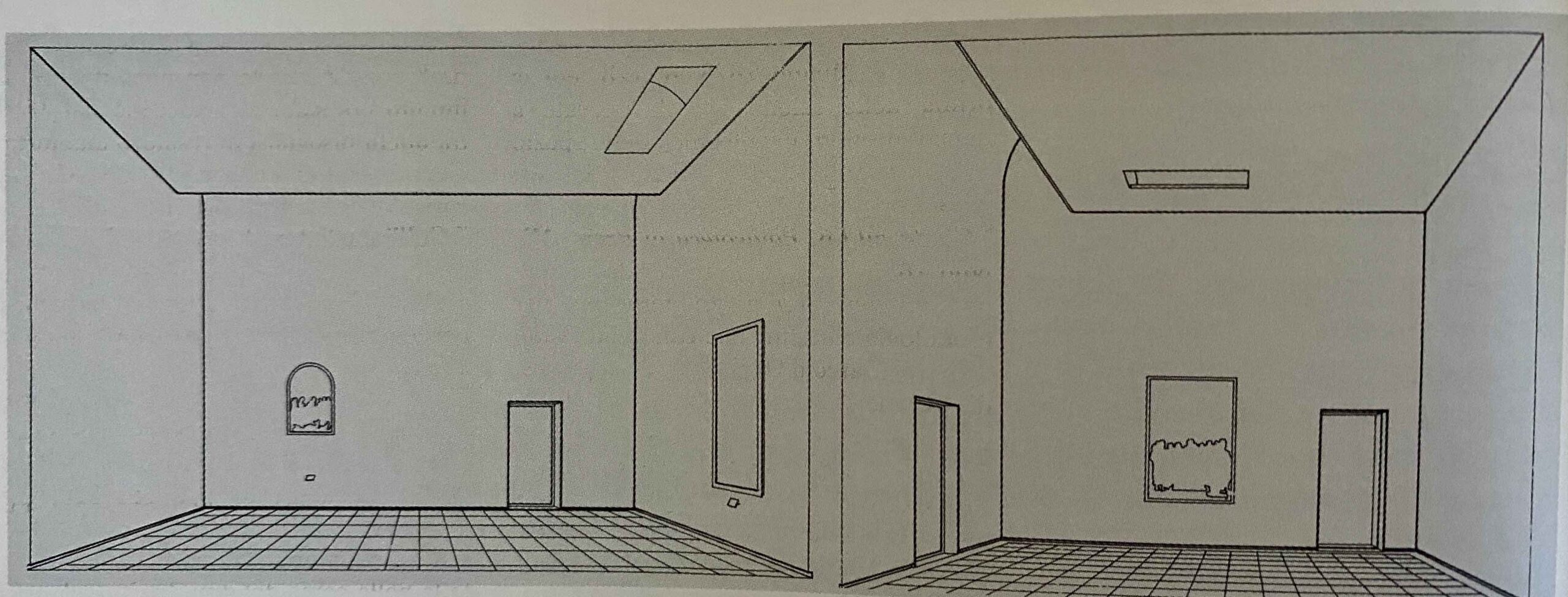

Yet rather than turning to the studiolo for this new layout, Portaluppi drew his inspiration from the two other small rooms in the Ducal Palace, the Chapel of Pardon and the Temple of the Muses designed by Francesco di Giorgio Martini for Duke Federico da Montelfeltro.

This strong spatial and dimensional echo, however, produced a far more stylised result, empty of any form of furnishing or decoration in the style of the period. The white walls themselves were reminiscent of the current condition of the palace in Urbino, which had lost all its original furnishings over the centuries, thus highlighting the proportional harmony and strength of the architecture.

1977

A MUSEUM ON TRIAL

To mark the Pinacoteca’s controversial closure ordered by Director Franco Russoli to draw public attention to Brera’s unresolved problems and to the broader debate over the museum’s role in contemporary society, Bruno Munari invented a tool for interpreting the Marriage.

The focus once again was on the mathematical, rational perspective in a historical interpretation in which the Montefeltro court’s figurative culture, filtered through the influence of Florence and the presence of Paolo Uccello and Piero della Francesca at court, led to Bramante and Raphael.

The experiment sought to force the visitor to view the picture through one eye from a single viewpoint; probably the viewpoint the artist had devised for the painting and which, through a grid made up of lines superimposed on the image, revealed its geometrical construction. It ensured a ‘correct’ view – as effective as it was artificial.

ANNI ’80

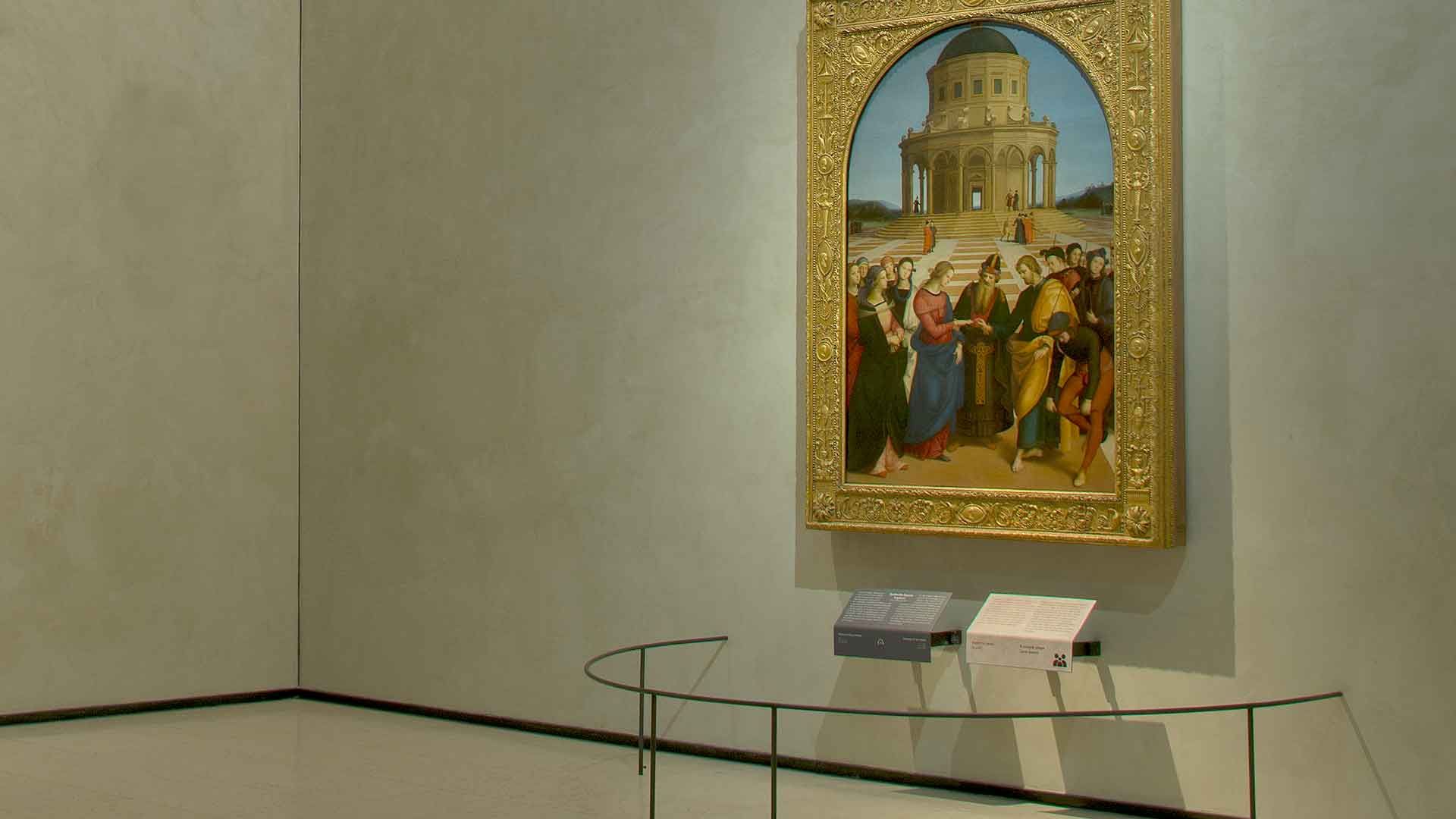

The renovation of the Pinacoteca di Brera layout after the Museum on Trial fell to Carlo Bertelli, who succeeded Russoli after the latter’s tragic premature death. Particular attention was once again lavished on the Raphael Room.

Bramante’s picture was moved back to the room housing work by the Lombard School, so that the reference to Urbino consisted once again of Piero della Francesca, Luca Signorelli and Raphael alone.

Devoid of any figurative element designed to conjure up the atmosphere of the palace in Urbino, the room’s pure white geometry – even the flooring was in white split stone – echoed only the concept of the rarefied purity of the rooms in the Ducal Palace.

In this space without any historical reference, even without the frames that had accompanied them since the museum first opened its doors, the paintings were intended to reveal their full expressive and formal strength. Absolute in their value as timeless classics and in their isolation, were lit by carefully balanced lighting – combining natural and artificial sources of light – coming from a carefully concealed source in the ceiling.

Raphael’s painting, deprived of the frame, made for it in Milan in the early 19th century, hung at the same height as it would have stood in the 18th century altar in San Francesco in Città di Castello, in an effort to evoke the painting’s history, albeit still only in a strongly conceptual manner.

TODAY

Day-to-day requirements have made a few changes necessary to Gregotti’s design. An increase in the number of visitors since the early 1980s has led to the installation of distancers on the ground, while Piero della Francesca’s painting has been replaced in its frame so that the frame can support and protect the wooden structure on which the picture is painted.