THE GREAT BRERA

The story of a humanist dream and a rare interest. Fernanda’s hard work, the marks of her lucid critical intelligence, the legacy of the 19th century and the development of the great project of Brera as a living museum.

Ettore Modigliani was restored to his post as director general on 12 February 1946, the day the Italian Government took back the management of its artistic heritage. In March of that year, Modigliani stressed to the Ministry that:

This money will not be spent on temporary work or on work whose use will be anything other than permanent, because that work must be seen as the first stage in the overall reconstruction of the Great Brera.

The ambitious turn of phrase with which Modigliani described his project was to be embraced as a challenge and a hope first by Fernanda and then by Franco Russoli.

On Modigliani’s early death in June 1947, Fernanda was appointed to the post of acting director general. In her new role she reminded the political authorities that help from the Ministry alone would allow her to complete the job and to open what she herself called the “Great Brera”. In Fernanda’s view, Brera had to prove that it could become a focal point for international culture and one of the glories of republican Italy.

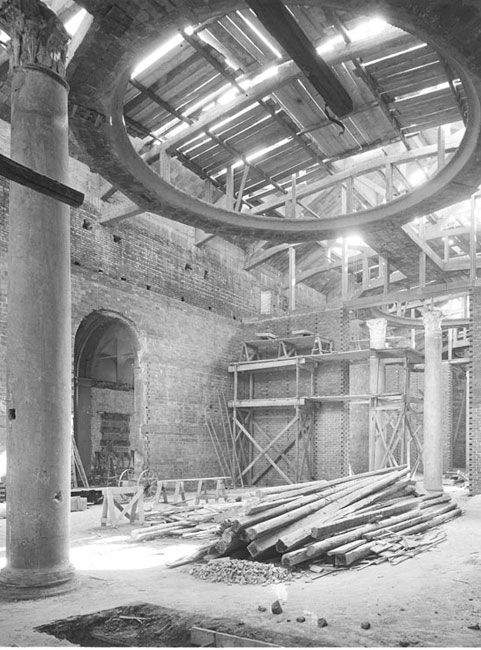

By December 1948 the Palazzo di Brera’s static consolidation had been completed and the thirty-four exhibition halls destroyed in air raids had been reroofed. It was only after four years of effort and extremely hard work in the scientific, technical, administrative, diplomatic and political spheres that Fernanda Wittgens officially reopened Brera before the highest authorities in the state, delivering a short yet vibrant speech in which she retraced the history of the building site, a moving communion of technicians, craftsmen and workers who had made the miracle of reconstruction possible in four years of working shoulder to shoulder with the museum’s management.

Fernanda Wittgens, speech delivered at the opening ceremony of the rebuilt Palazzo di Brera; typewritten, 9 June 1950

Fernanda Wittgens’ vision was both innovative and proactive. In her view, the reconstruction and expansion of museums throughout the country must invariably go hand in hand with a constant commitment to keeping personally abreast of developments in the field of cultural heritage protection, also by examining what was being done abroad, including in the United States.

The Pinacoteca was brought to life by a serious of unprecedented exhibitions and educational events, most of them innovative from both a museographical and a scientific standpoint. Fernanda set in motion a revolutionary educational programme in the newly reconstructed Brera in 1951.

She organised tours guided by experts – often by herself in person – for children from Milan’s kindergartens, in the course of which she urged her young visitors to jot down their impressions in drawings. Courses and Sunday tours were organised for the CRAL working men’s clubs, pensioners, the handicapped, workers and craftsmen. An Education Department was officially established in Brera in 1955.

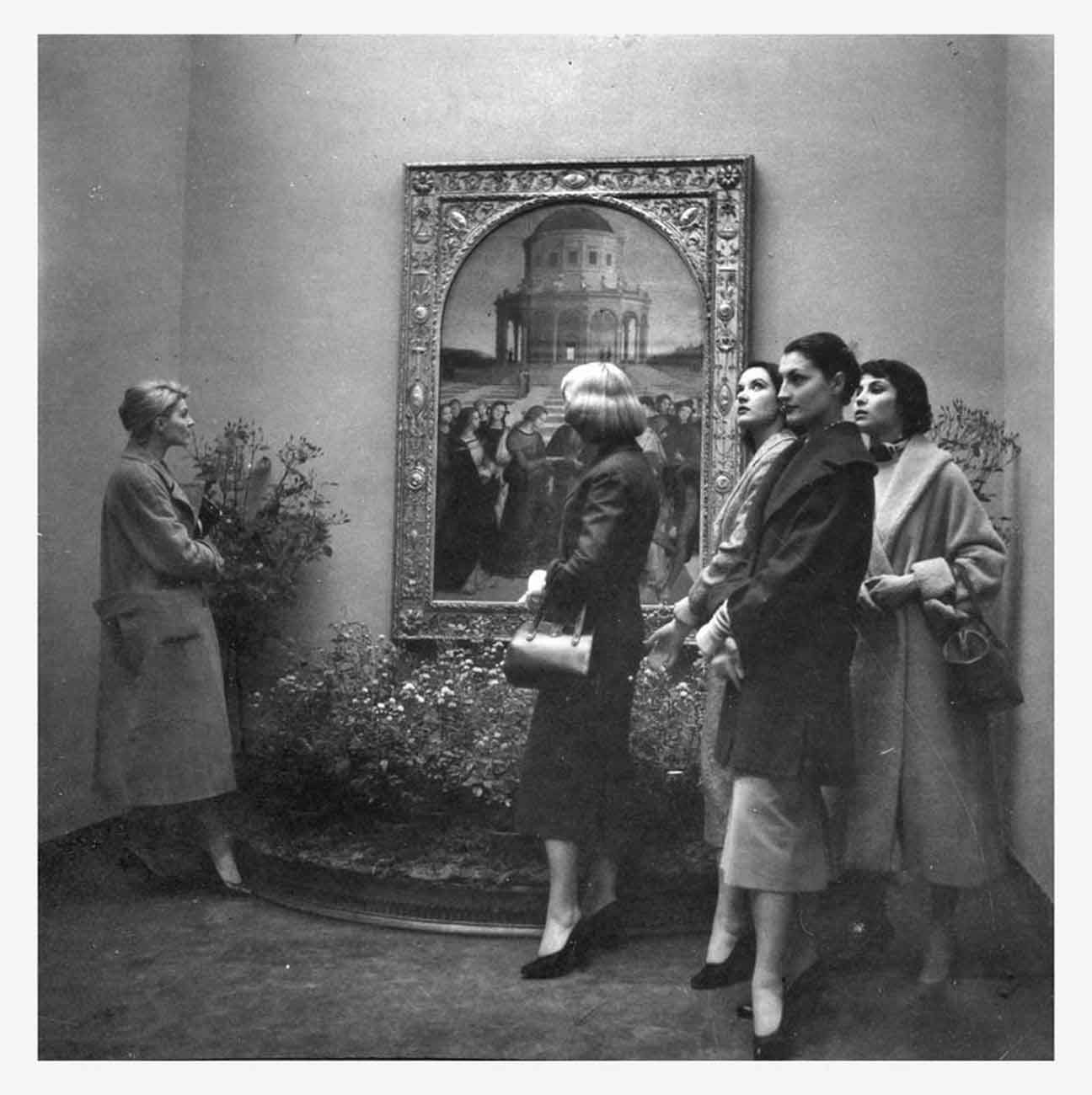

In the spring of 1956 Fernanda organised an event entitled Flowers in Brera, a huge public success that drew 20,000 visitors on its first day and that was also a successful example of cooperation between a private sponsor and a state-owned museum. In the space of a mere seven days the Brera attracted 180,000 visitors, some 40,000 of them on Sunday alone.

Fernanda continued to pursue her struggle right up to a few months before her death, this time to persuade the Treasury to buy Palazzo Citterio, a crucial link in the construction of Modigliani’s old dream of the Great Brera. In conjunction with Portaluppi, she resubmitted a Development Plan for Brera initially presented in 1950, based on the construction of a lifeline linking the Pinacoteca, the Accademia di Belle Arti, the Biblioteca, the Osservatori Astronomic and the Istituto Lombardo di Scienze e Lettere.

From her letters:

The humanistic dream of harmony between Art, Literature and the Sciences which Maria Theresa and Napoleon forged in the living stone of the Brera is our dream", she wrote, "and the Pinacoteca di Brera would like to make a lively contribution to that harmony with its exhibition halls, its restoration laboratory and its scientific research, and with educational activities designed for the people (...) so that the museum can finally partake of the dynamism of modern life and aesthetic culture can circulate like a living yeast in society.

In addition to which, there was her interest in 19th century painting, an interest not widely shared by the brass in the Fine Arts Directorates General at the time yet crucial, in her eyes, for understanding the century that came after it.

The history of the 19th century is brought to a close by the gift of Boccioni’s admirable Self-portrait donated by Vico Baer, the protector of the Milan school’s leading artist and an intelligent pioneer in the collections of modern art that are now the boast of Milan. [...]

Fernanda Wittgens

Donations to the Pinacoteca di Brera, 1955

And finally, in 1956, she wrote Ferruccio Parri a key letter which we may consider to be her spiritual and political testament. Parri asked her to stand with the Fronte Laico in the local election. She replied as follows:

My dear friend, I have thought the matter over at length and I feel that I owe it to you to expound my thinking in full. For me and for the best in Italy you are not a man, nor yet a symbol, but the very embodiment of the dignity of our homeland, and one cannot be reticent or seek excuses with you.

[...] I shall always be able to bear witness for you to the values that you embody in terms of Italy’s history: I daresay even at the risk of going back to prison and into exile – in other words, experiencing until our earthly time is up the tragic fate of exiles that we of the Liberation have all experienced in this reactionary decade. Even at the cost of our lives if that were necessary[...].

But I cannot bear witness for you as the leader of a party because I do not believe in the party of intellectuals. [...] Today I do not feel able, as an artist, to set out down the party track because my freedom is the absolute precondition for the life of my very being.

[...] After ten years of this experiment of grass-roots elevation, I have only too clearly understood that the task of the progressive intellectual and aristocrat is, if anything, to join with the masses and to select the forces which, educated by us, can create a new society. That is why I dare write to you and, unfortunately, disappoint you; because for me, at this juncture, this is an absolute truth, a lifetime commitment, an act of faith. […]”.

Fernanda Wittgens

Letter to Ferruccio Parri,, 16 March 1956

Fernanda died in the early hours of the morning on 11 July 1957. Her coffin lay in state before the entrance to the Pinacoteca, at the top of the grand staircase in Palazzo di Brera. Thousands of people signed the register of condolences, and a large crowd followed the hearse to San Marco. She is buried in Milan’s Cimitero Monumentale.