GIULIA MAFAI

Life in the art world in postwar Rome

From Giulia Mafai’s conversation with James M. Bradburne on 9 June 2021.

The story of the vibrant life of the art world in Rome in the post-war period as told by Giulia Mafai to the director, James M. Bradburne. The intellectuals and their two worlds, the city’s neighbourhoods, the strong sense of community, working with Rodari, the opportunities, the cinema and, finally, her memories of her family and her father.

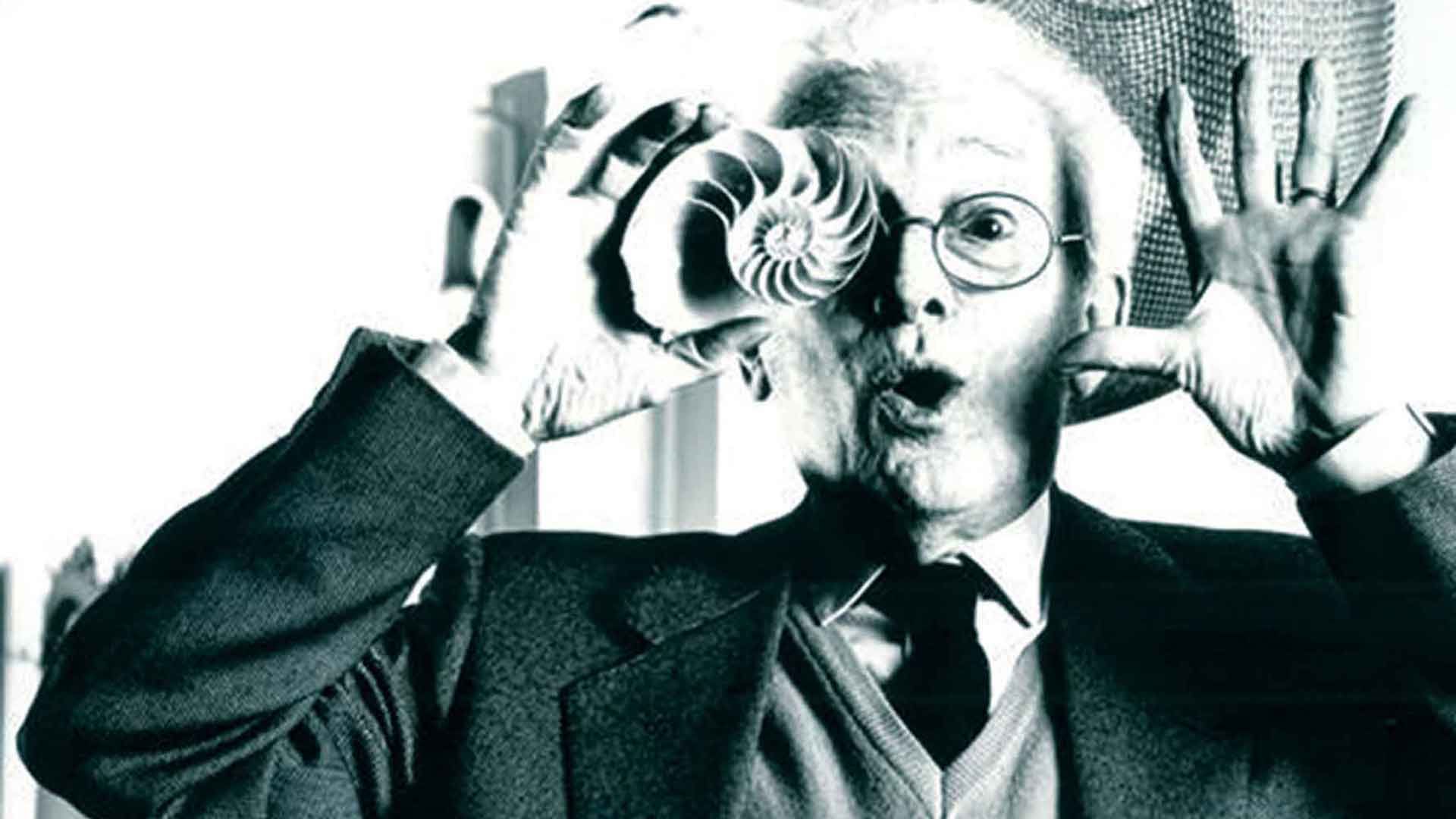

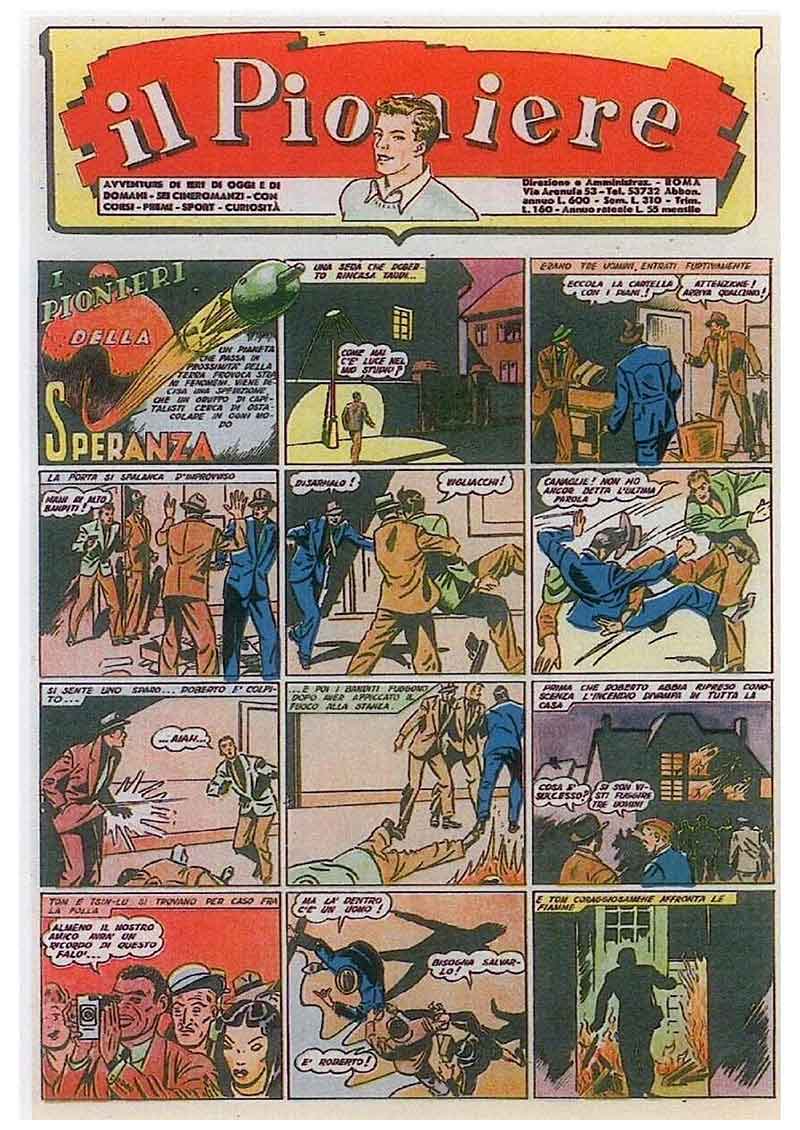

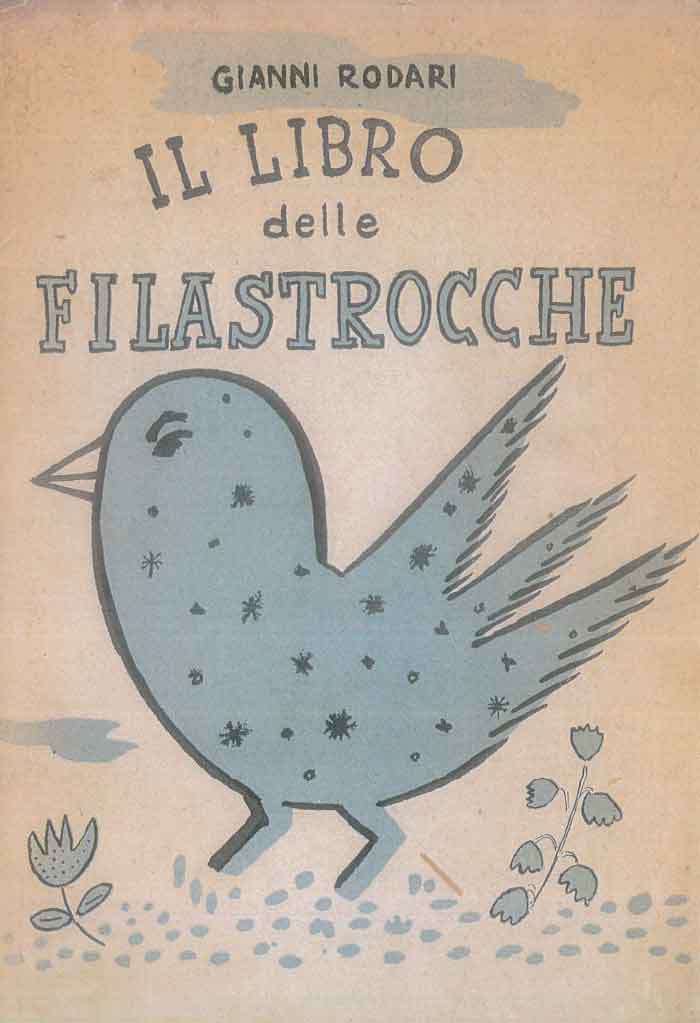

Giulia Mafai, artists Mario Mafai and Antonietta Raphaël’s third and last daughter, embarked on a career as a costumier and set designer in 1950, working on some of the best-known Italian films and with such directors and actors as Vittorio De Sica, Mario Monicelli, Sophia Loren, Marcello Mastroianni, Elliott Gould, Harvey Keitel and Keith Carradine. She devised and curated the Laboratorio del Carnevale di Venezia from 1978 to 1985; she worked with Gianni Rodari on Il Pioniere [The Pioneer] i n 1950 and 1951; and she published texts, illustrations and comic strips including Sambo, Conoscete gli animali? [Do you know the animals?] and Il re detto orecchie d’asino [The King also known as Donkey Ears] in 1951.

THE INTELLECTUALS AND THE TWO WORLDS

Rome in my day revolved around the concept of the neighbourhood. The neighbourhood was a self-contained unit for those who lived in it. My father and I lived in Via Margutta, then there were those who lived in Piazza Mazzini and so on.

There were two groups of intellectuals in Rome. One in Piazza del Popolo with the Bar Rosati where you might bump into Moravia, Morante, Pasolini, Enzo Siciliano and painters like my father for example. The other, which was wealthier, was in Via Veneto where the bars were very expensive, the hotels were 5-star affairs and the people were more the cinema crowd: Fellini, Monicelli and the American producers and big-name actors.

You’d go to Rosati for a cup of coffee and if you were bright, you’d think up a quip and worm your way into their conversation. Or else you’d go to Otello, an amazing place where you could eat on tick and pay the bill only after you’d found the money, possibly by selling a painting.

I’d occasionally go to the Osteria Fratelli Menghi and all I had to do there was say: “Dad’s paying! Dad’s paying! Dad’s paying!” and being thin and having weak lungs, they’d pet me: “Go on Giulia, eat up! Don’t you like it? Wait, I’ll bring you this… I’ll get you that…”. It felt like living in a big village, a weird and very deep sense of community.

GIANNI RODARI

That was where I met Rodari. He was a poet, an artist, you know? The way a painter sees light and colour, he saw words that became poetry.

At the time he was busy with the Il Pioniere [The Pioneer] newspaper project and looking for people to help him. It was a left-wing paper for children. His poems were lovely. He wrote with delicacy and grace, but there was always a social twist at the end. I offered my services and he hired me. I earnt 2,000 lire per comic strip. It wasn’t much but it allowed me to offer people a cup of coffee. We helped each other out.

Modugno used to come to my studio in Via Ripetta with his songwriter, to scrounge cigarettes because he never had any on him. Rodari and I, on the other hand, swapped books. I lent him the ones I could afford. He was an artist in my view, capable of turning words into poetry. He was very ironical, and he didn’t lecture, he offered me advice. He taught me that teaching has to take the shape of a suggestion that persuades people to process, to think, to develop their own ideas. “What do you think, Mrs. Mafai? Is that all right? Have I managed to get it right?” He was a charming man, a dear friend.

We published his first book together and it had my illustrations.

I also worked in a play he wrote with a friend of mine. It was called Il Cortile, I think. We performed in a theatre in Genoa. It was probably the only time he ever did anything with the theatre. You see how it was among friends? You’ve got a friend in the theatre? “Come with me and we’ll write something together”. A friend in the film industry? “Come with me and we’ll write the script”. It was all very varied and spontaneous, without any ‘bosses’, we were all part of the same collective as we used to call it.

THE CINEMA

First I attended the Accademia di Belle Arti in Genoa, where I lived with my mother. Then I began to work as a costume designer for films and the theatre at the age of only 19, while studying at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia. By the age of 21 I was already doing the costumes for a play, a show, with up to 40 actors at a time.

No one would give a 21-year-old girl such huge responsibility today. But that’s the way it was in those days, possibly because there was no alternative. We youngsters unwittingly embodied a new kind of culture in an Italy that was still provincial. We read Mayakovsky, and we enjoyed the Spanish poetry of Neruda and Garcia Lorca almost in secret. We had fresh energy and new ideas.

I still remember my first film on account of my mistakes. I made a lot of mistakes, one after the other… I was told to prepare the costumes for a film set in the Middle Ages, which was very popular back then. I made so many mistake that every time I saw the director, I was so ashamed I’d cross the road. Until one day, a couple of years later, he asked me: “Giulia, have I offended you in some way?” I answered in embarrassment: “No, I’m the one who’s ashamed. Every time I bump into you, I remember all the mistakes I made, and I can’t muster up the courage to say hello to you!”

THE FAMILY

“Not this music but that music. Not this painting but that painting. Not these clothes but those clothes.”. I truly believe that if you’re going to criticise, you have to be able to offer an alternative. That’s how it was in 1968, a true moment of rebellion, possibly the last such moment. It was a very different stance from the one that had preceded us. It was powerful in that way. We started out by saying NO, we strongly criticised the mediocrity in the bourgeoisie and in morality. We girls were opposed to the idea of marriage.

My two sisters, Miriam and Simona, were amazing people. Dad used to tell us that Simona was already studying socialist democracy and spending a lot of time in the library at the age of 14. At 14, for heaven’s sake! I wasn’t like that at all. According to my parents I was what they called ‘detached’. I was always in the garden, with the cats. They couldn’t understand what I was up to. They called me Zuleima, a belly-dancer’s name, instead of Giulia, and to get me to study they threatened to marry me off. I laugh, but for them, if I didn’t become learned, if I couldn’t speak foreign languages or play the piano or the violin, then I might as well be thrust onto the marriage market.

My parents only got married when we were already quite old, in 1935. They’d been together for 10 years. Their decision was due to a new law that came into force at that time enjoining all foreigners who’d been in Italy for less than 20 years to register or else they’d end up in the camps.

THE POSTWAR ERA

Painters were no longer acceptable, literary buffs were no longer acceptable. And as they do after every war, people wanted total renewal, not just of society per se but also, of course, the renewal of intellectual society. My father, Mafai, felt out of his depth like so many other artists. Other artists had the strength and the courage to continue being themselves. De Chirico didn’t change an iota, nor did Morandi. Campigli, and I could name other artists of the time, stayed in their orchards, as Machiavelli would have said.

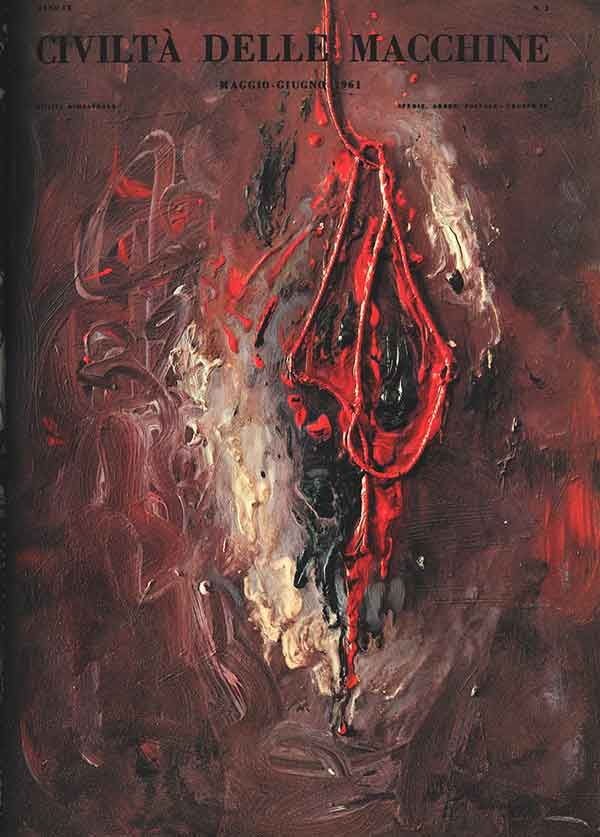

But not Mafai. Mafai couldn’t find it in him to go back to painting dried flowers and demolitions. He felt all that was obsolete. For instance, in the 1950s Sinisgalli asked him to do the cover for “Civiltà delle Macchine” [Civilisation of Machines] in which there is a detail that’s reminiscent of the Fantasies. On the cover the dried flowers became ropes, but the essence was still the same. Instead of a dried flower tossed by the roadside, there was a rope tossed by the roadside.

He came in for a lot of criticism even from his best friends, but a few of them, including Antonello Venturi and Argan, continued to support him.

In the end he left; he said:

“Good-bye and thank you, I’m off”.

In memory of Giulia Mafai, 13 January 1930 – 26 September 2021