FERNANDA WITTGENS

A lifetime of intellectual and civic commitment (1903-1957)

The story of Fernanda, her joining Brera and the start of the war. Her struggle against fascism and her arrest. A tireless woman of great introspective depth, committed both professionally and politically, tells her story in the letters she wrote to her family while under arrest.

Fernanda and Brera

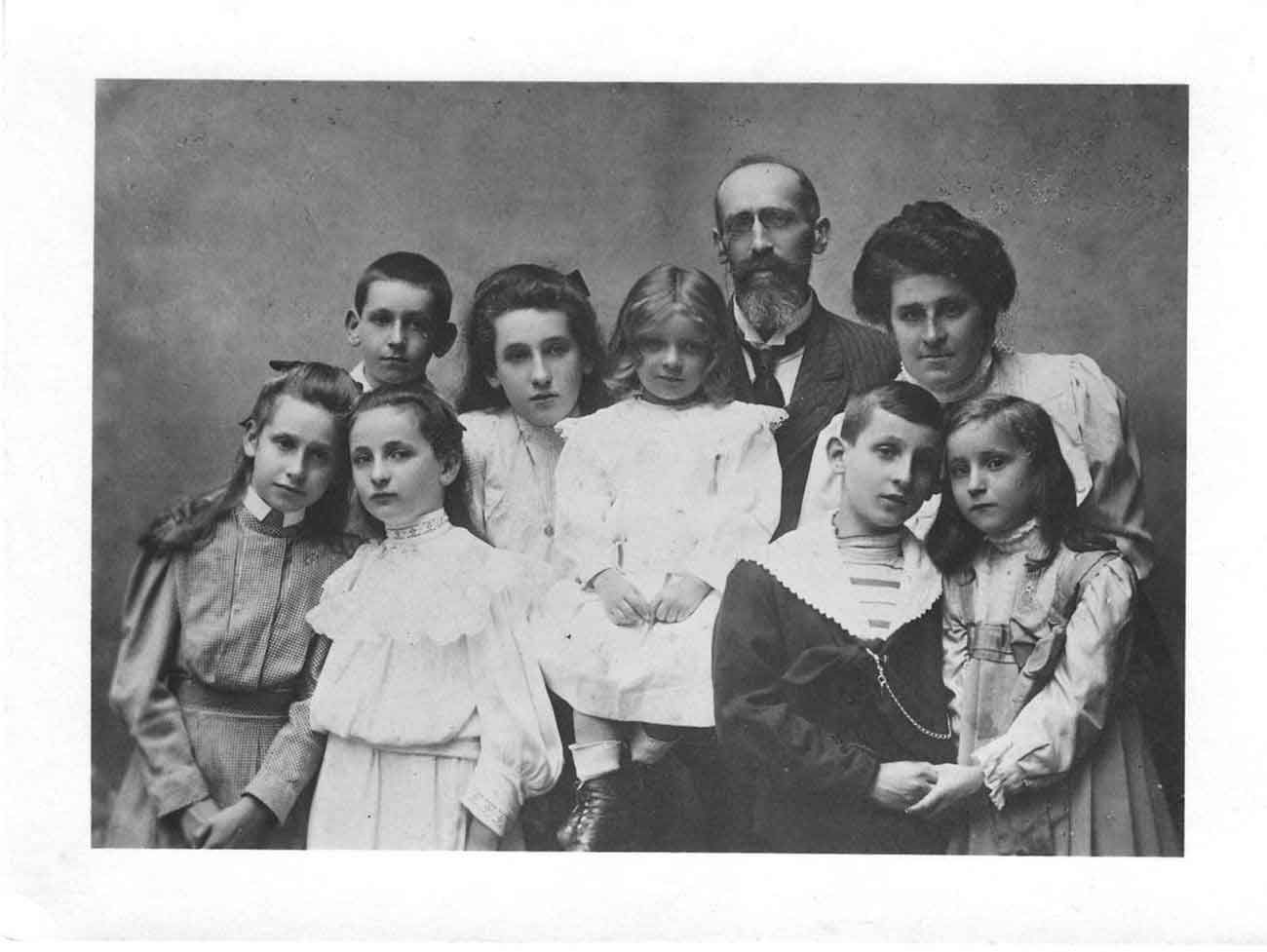

Fernanda Wittgens was born in April 1903. Her father, who taught literature at the Liceo Parini, raised his children not only to respect the state and its democratic values as propounded during the Risorgimento, but also to love art thanks to their Sunday visits to museums. Under the guiding hand of Paolo D’Ancona, Fernanda graduated cum laude from the Accademia Scientifico Letteraria di Milano with a thesis on art history in 1926.

It was Mario Salmi, then an inspector with the Brera, who introduced the young but already brilliant scholar in 1928 to Ettore Modigliani, the director of the Pinacoteca and director general of the Gallerie della Lombardia since 1908. Fernanda was hired at the Brera on a short-term contract, yet she was tasked with performing the technical and administrative duties of an inspector.

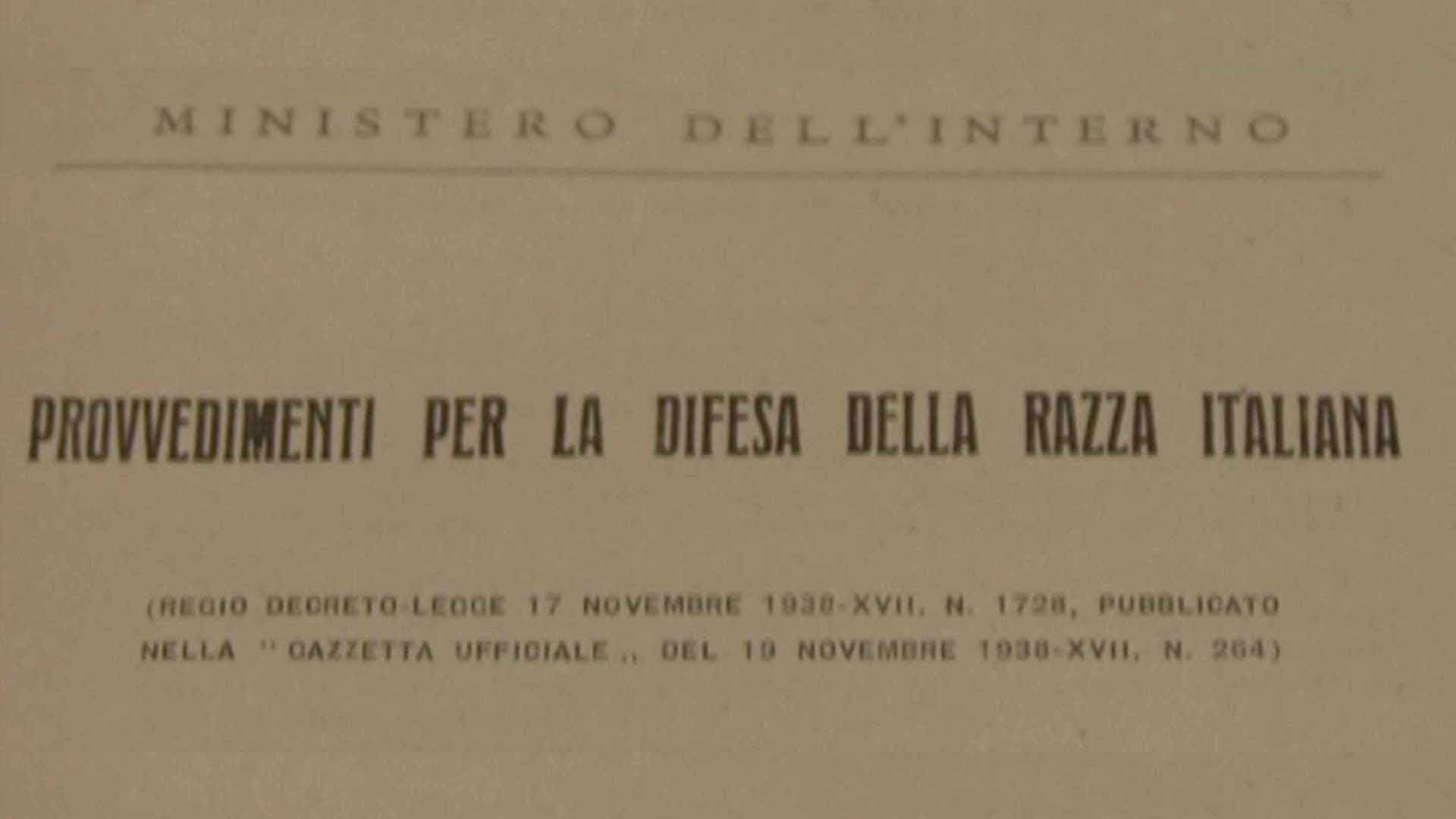

Modigliani found her to be the ideal assistant, at once technically competent, scholarly and prepared to work hard. When he was removed from the Fine Arts Administration on a charge of anti-Fascism in 1935 and interned in L’Aquila, Wittgens carried on his work while keeping him constantly abreast of events; and she remained intellectually close to him even when he was finally expelled from the civil service in 1939 on account of the racial laws that had just come into force.

In 1940 Wittgens entered a competition and won the nomination for the Pinacoteca di Brera, the first woman staffer with the Musei e Gallerie ever to achieve such high office in Italy. People were immediately struck by her working style and the vibrant humanity that she cultivated in her relations with her superiors, her colleagues, and Brera’s staff as a whole.

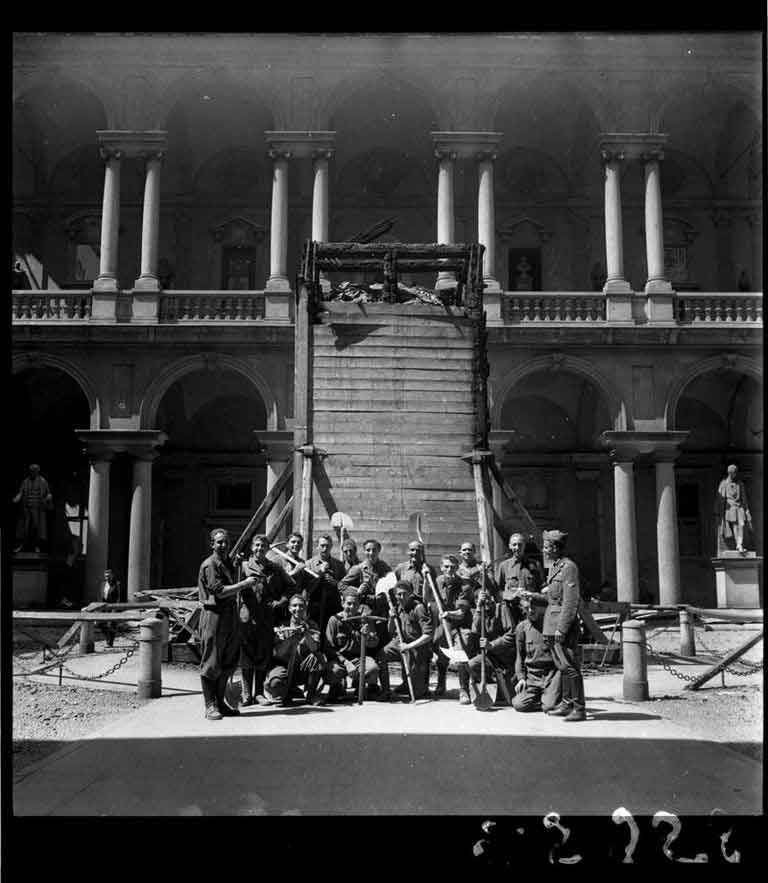

Fernanda and the War

As war loomed, Fernanda took a personal interest in organising the removal of Brera’s works of art to different safe houses, and it was she, after the armistice, who once again – in the absence of a central authority, particularly for the protection of art heritage – shouldered the huge task of preventing the works in the Pinacoteca, the Poldi Pezzoli, the Quadreria dell’Ospedale Maggiore and other collections, from being looted and shipped to Germany. Under enemy air raids, with only a skeleton staff and using makeshift vehicles picked up here and there, Wittgens moved the works of art to a new and safer location.

Her personal prestige and the influential friendships on which she could count placed her in what was in many ways a privileged position, and this was to allow her from the day war broke out to help her relatives, friends, Jews and other victims of persecution to leave the country.

In the summer of 1944, a tip-off from a young German Jewish collaborator whose flight abroad Fernanda had helped to organise led to her arrest at dawn on 14 July. Tried by a special tribunal, she was sentenced to four years in prison. She was to remain in prison, initially in Como and then in Milan, until February 1945, when she was moved to a Milan clinic and confined there until the Liberation.

The letters she wrote from her cell paint a picture of a woman eager to ensure that her family understood the reasons and motivations that fuelled both her professional and her political commitment. Art, in Fernanda’s view, plays a social and moral role and must thus be offered to all as a tool for knowledge and personal growth. Her writing while in prison also contains personal thoughts of great introspective clarity on her condition as a woman.

When a civilisation collapses and man becomes a beast again, whose duty is it to defend the ideals of civilisation, to reaffirm that all men are brothers, even if he is called on to pay the price for doing so? At least the so-called intellectuals, in other words those who have always claimed to serve ideas rather than base interests, and in that capacity have taught young people, written and risen above the common ranks. It would be too convenient to be an intellectual in peacetime and a coward, or even just neutral, when danger looms. The mistake my sisters and you are making is to think that I am dragged by the goodness of my heart and by pity into helping people without being aware of the risks involved. The truth of the matter is that it is a firm proposition which reflects my whole way of life: I cannot live any differently because I have a brain that thinks like this and a heart that feels like this.

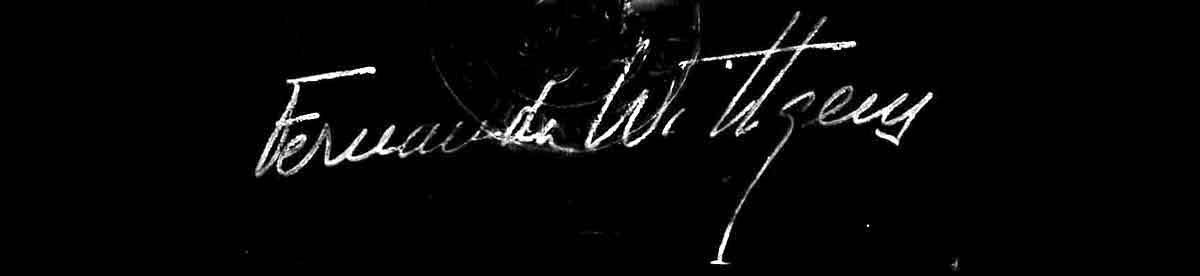

FERNANDA WITTGENS

Letter to her mother from San Vittore prison, Milan, 13 September 1944