SANTA MARIA

IN BRERA

Zenale’s organ loft panels adorning the organ in Santa Maria di Brera are the precious surviving trace of a far longer and multifaceted story that led to the birth of the Palazzo di Brera as we know it today.

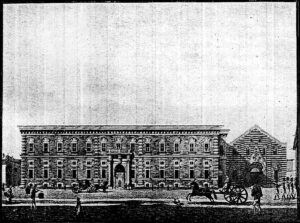

If we walk around the outside of the palazzo, we get the impression that we are looking at a building in a single style, the result of Francesco Maria Richini’s 17th century renovation, but it is in fact the product of a series of structural changes implemented over the centuries.

What are the stages in that process, and how have the different uses to which it has been put forged its identity?

The Legacy of the Umiliati

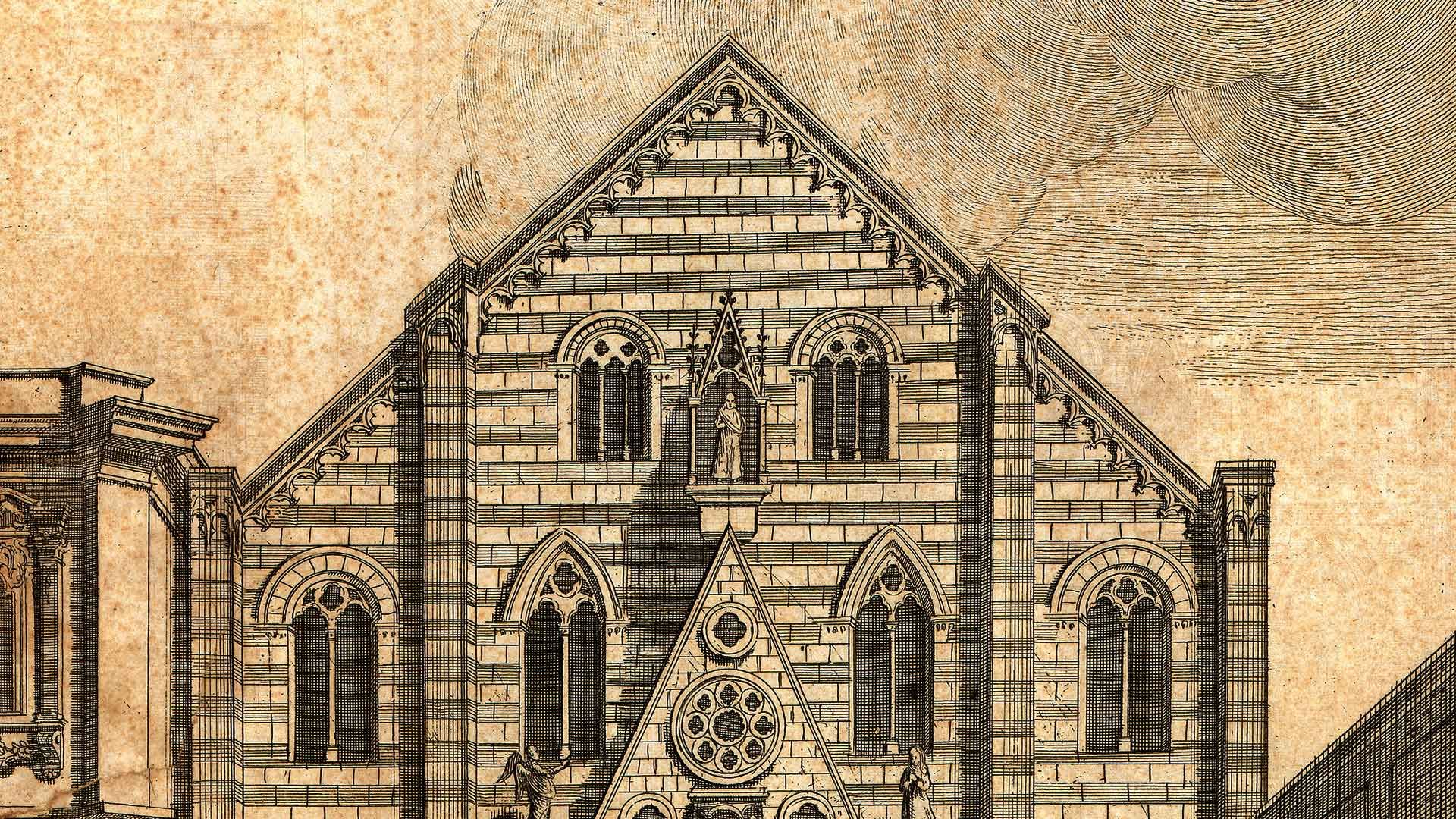

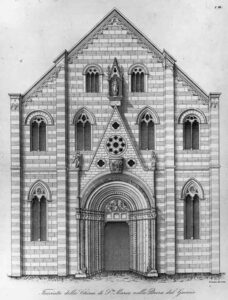

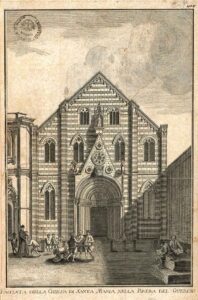

We know from illustrations that the façade of the church of the Umiliati, who settled in Brera in the 12th century, was still standing in a corner adjacent to the south of the palazzo in the early 19th century.

Despite changes of ownership with the suppression of the monasteries, first for the Jesuits and then for the Austrian Government, the building maintained its architectural and functional integrity until the early 19th century.

A new function: the Royal Gallery

The church was deconsecrated for good in 1806 and the façade was demolished to make way for the future Royal Gallery. This was erected over the next few years based on a plan designed by the architect Pietro Gilardoni 1809/10 to a commission from Napoleon himself.

With this Gallery, Napoleon aimed to create a modern, vibrant entity expressing the new government’s strong desire for cultural and architectural innovation, given that Milan was now its capital.

So the renovation of the Palazzo di Brera was part of a plan involving the city as a whole, thus an up-to-date map of Milan was required to serve as a guide for the city’s new town planners; Brera’s Astronomers were tasked with producing such a map in 1807.

From the demolition of the church to the new rooms

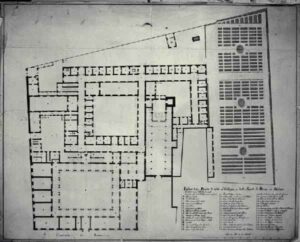

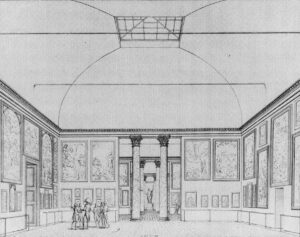

The project redefining the Brera complex as the Royal Palace of the Sciences and Arts resulted in the construction of four large halls and other smaller rooms occupying the upper part of the former church.

The halls were designed to host large altarpieces and paintings from churches in central and northern Italy, while the smaller rooms were meant to house other collections such as self-portraits or plaster casts.

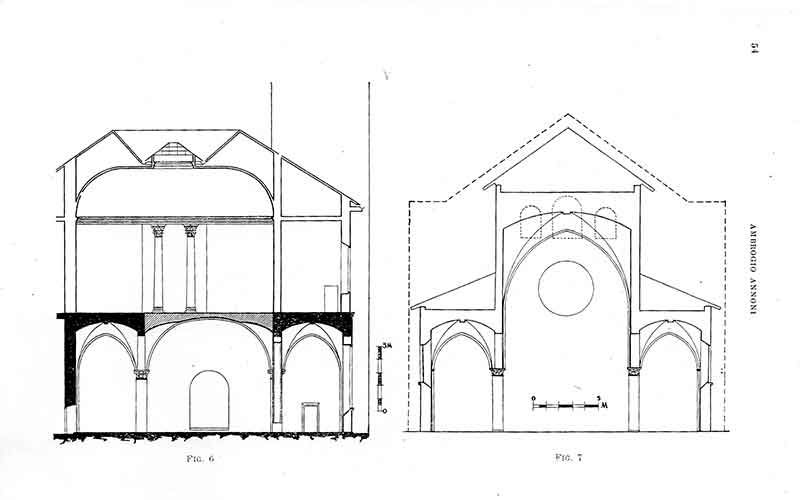

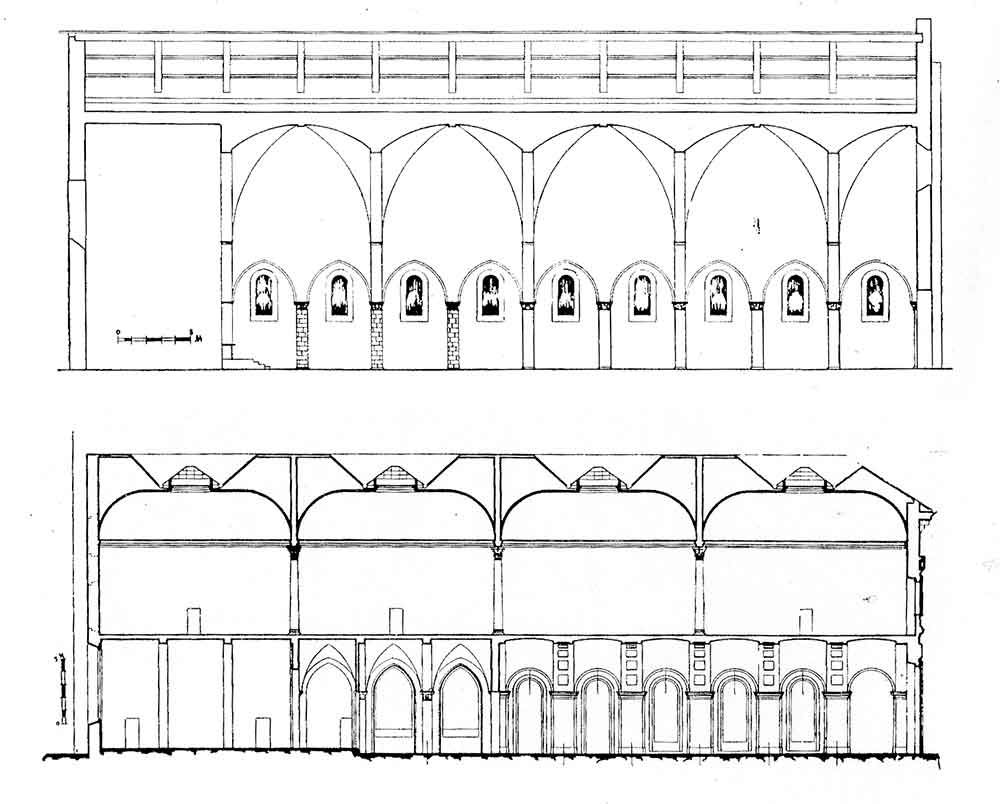

The church was split horizontally and the vaults and trussed roof were dismantled so that the rooms occupied the entire surface of the church, perfectly matching the Accademia’s rooms on the first floor which had already been converted for use as exhibition halls.

To complete the ceiling, new walls were built along with cloister vaults with central skylights, supported by three large cross-arches and reinforced buttresses, while a new public square was designed to take the place of the church’s original parvis.

The Gallery was officially inaugurated in August 1809 to tie in with the Emperor’s birthday, although it effectively opened only the following year because it proved necessary to extend the building towards the square by one bay, reconstructing a new front for the church façade – despite the opposition of the Adornment Commission – which an inscription engraved on the lintel over the door attributes to Giovanni di Balduccio of Pisa with a date of 1347.

The Museum of Antiquities

But what happened to the bottom part of the church?

The Commission allotted the surviving part of the church to the “Museum of Antiquities” because its interior rich in arches and columns was perfectly suited to house fragments of Classical and medieval sculpture.

A new vault was built over what had been the nave of the church and the original cylindrical columns were reinforced. A depiction of the New Archaeological Museum of Milan in the Palazzo di Brera was published in the ”Illustrazione Universale“ in 1867.

Behind the exhibition space there was a “large room for storing pictures and for restoration”, a “large warehouse for use by the Accademia di Belle Arti” and the School of Architecture, while the former sacristy was converted into the School of Perspective with an antechamber.

And finally, the bell tower set into the last eastern bay, which was originally supposed to be demolished, was kept for use by the Accademia on the ground floor, being raised and reworked to lend it greater structural stability so that it could be converted into the Astronomical Observatory.

What is left of the church today?

Despite the profound changes suffered by the church in the 19th century, we can still make out some of its original elements today, for example the south wall in brick, where we can admire the corbel table and nine rectangular buttresses, interspersed with round-headed windows with decorated surrounds and a fragment of the black and white marble cladding from the façade.

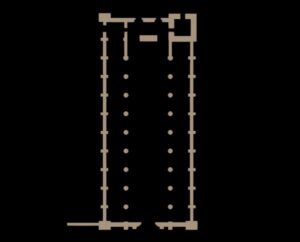

In the lower part, we can identify the division of the church into a nave and two side aisles which still have part of their original cross-vaulting, along with the chancel and fragments of rib vaulting, column bases and capitals.

Brera in the 20th Century

In 1939, Ambrogio Annoni, an architect and lecturer at the Politecnico di Milano, devoted a case study to the church in his course on “Monuments’ Stylistic and Constructional Features”, proposing a hypothetical reconstruction of its original ground plan and structure.

This was the first art historical examination of the building based on a survey of its legible traces. The study recommended not simply preserving the surviving parts of the church but meticulously retrieving their legibility, and in the 1970s the Soprintedenza ai Monumenti restored the complex, bringing back to light some of the parts that had been swallowed up in the 19th century transformations.

Santa Maria’s central role

Given that Santa Maria is the foundation, the very hub of the whole complex, we wondered whether it would be possible for it to recover that role, and how to bring that about. Attempts were made to link the two halves of the church by using them both as exhibition halls.

When reorganising the museum layout in 2018, we decided to replace some of the frescoes from Santa Maria di Brera in the corridor next to the Napoleonic rooms, i.e. the former south aisle of the church.