The Architecture of the Soviet Avant-garde

The study of Soviet architecture in the 1920s – avant-garde architecture – was largely neglected in the West until the mid-1960s, but from then on a number of studies began to focus on it in Europe, in the United States and, gradually, also in the Soviet Union.

One important aspect, however, continues to be little studied even today, and that is the work of the considerable number of foreign professionals who went to work in the USSR after 1928. Kurt Junghanns highlight the importance of the presence of foreign (especially German) architects in the Soviet Union in a study. He argues that:

The Foreign Architects’ Section in the Union of Soviet Architects [Obshchestvo sovetskikh arkhitektorov] from 1933 to 1936 counted some 800 to 1,000 members, despite the fact that not all the foreign architects were member [of the Union]. Typically, about half of them were Germans.

Even though the mass emigration of architects at the time was a purely German phenomenon, other European architects moved abroad throughout the 1930s probably for the same set of reasons as their German counterparts.

First of all, the impact of the Great Depression that began in the United States in 1929 was beginning to make itself felt, hitting Germany precisely in the ‘30s.

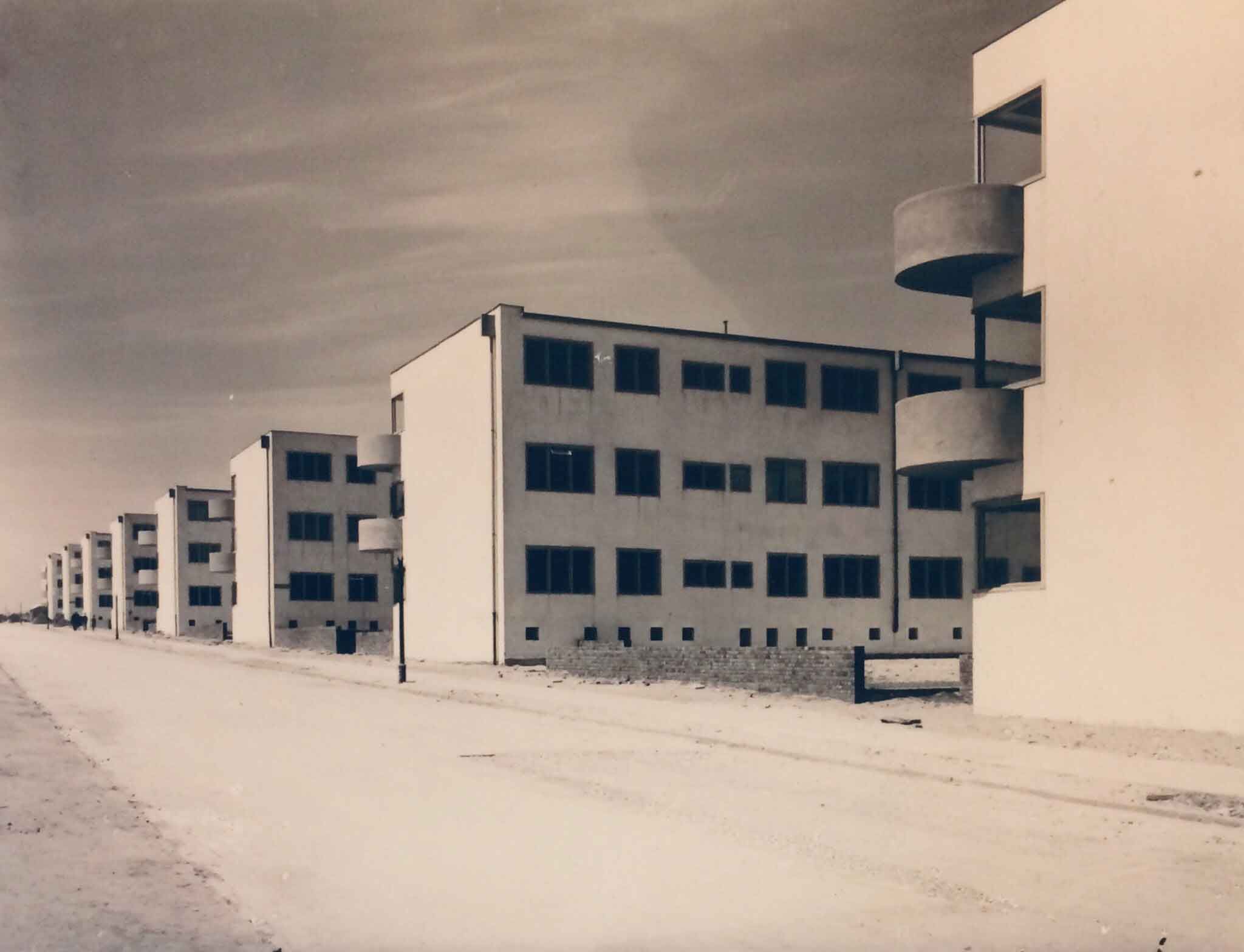

By 1932, about 45% of the active population on German soil was jobless and the creation of council housing schemes – one of the greatest successes of the Weimar Republic – had practically slowly stopped.

Nevertheless, that alone does not suffice to explain why the mass emigration was restricted to German architects and why they all headed for the Soviet Union. After all, the economic crisis in Great Britain at the time was just as bad as the depression in Germany.

Hitler’s rise to power in January 1933 is probably another reason behind the mass migration, though in fact the “big names” in German architecture were already leaving Germany at the beginning of the 1930s. Ernst May and Hannes Mayer, for example, left in 1930, thus before Hitler came to power.

One of the deciding factors behind this mass migration may well have been the way the USSR was perceived by a large part of the population in Western Europe, including a considerable proportion of the working class and a substantial number of intellectuals – including architects.

Architects continued to be driven by their belief in the principles of the modern movement, or Neues Bauen as it was known in Germany, as well as by the nature and social structure of their chiefly lower class customer base.

Perceptions of the USSR in the 1920s

A great deal of what we know about the first decade in the history of the Soviet Union today was unknown outside the USSR’s borders at the time.

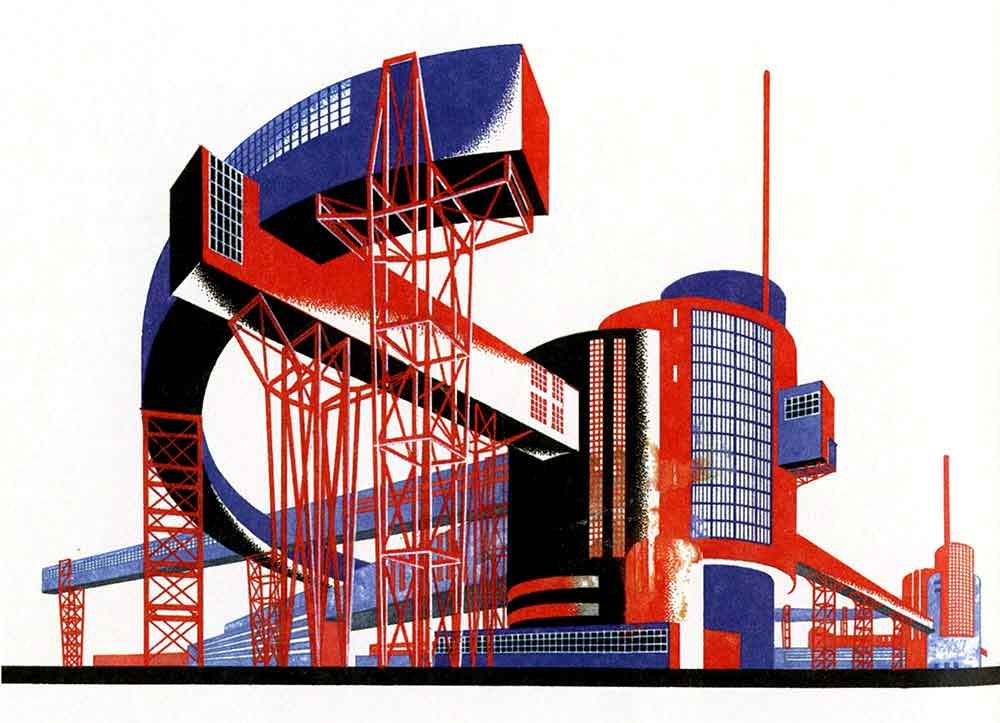

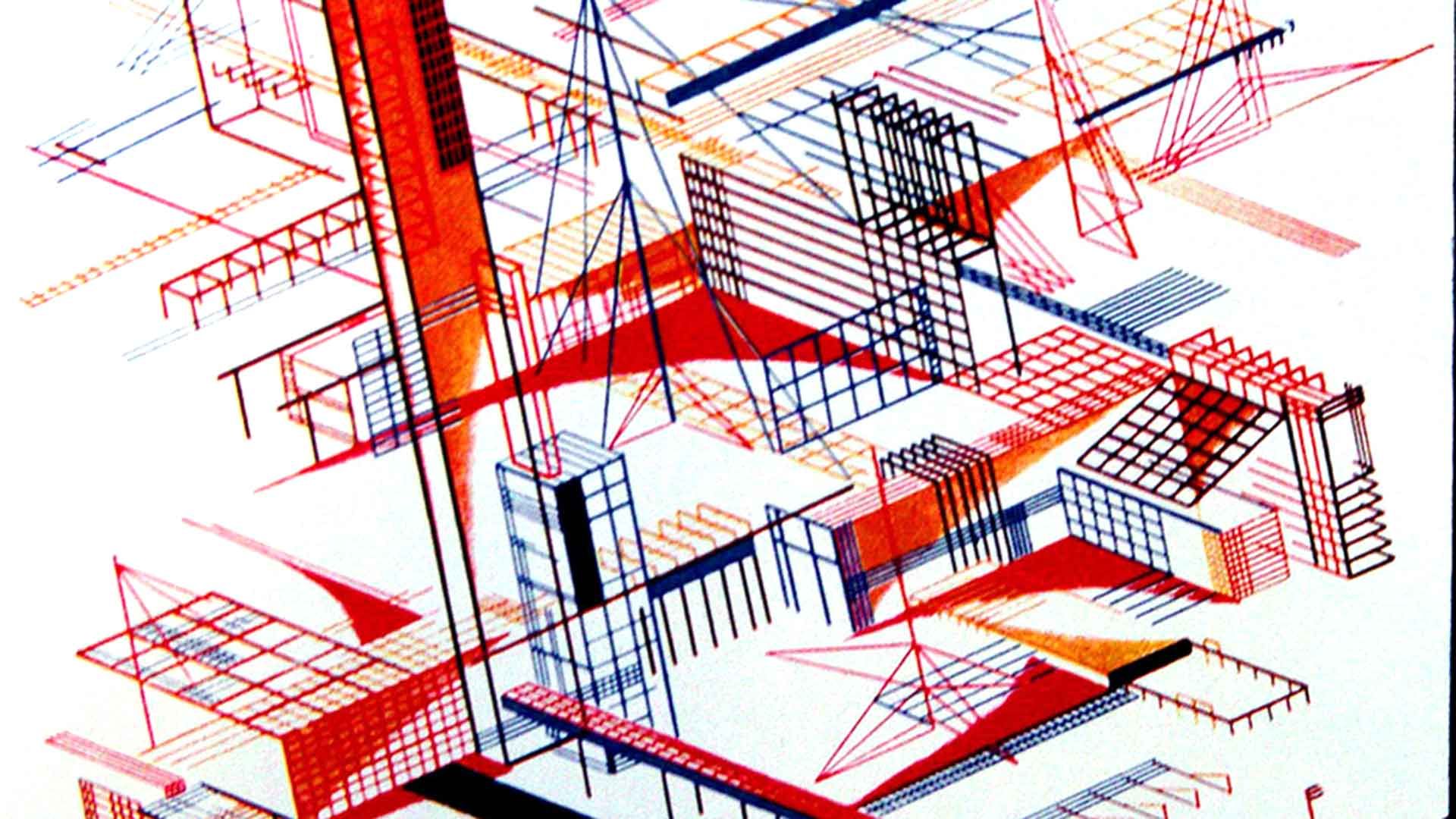

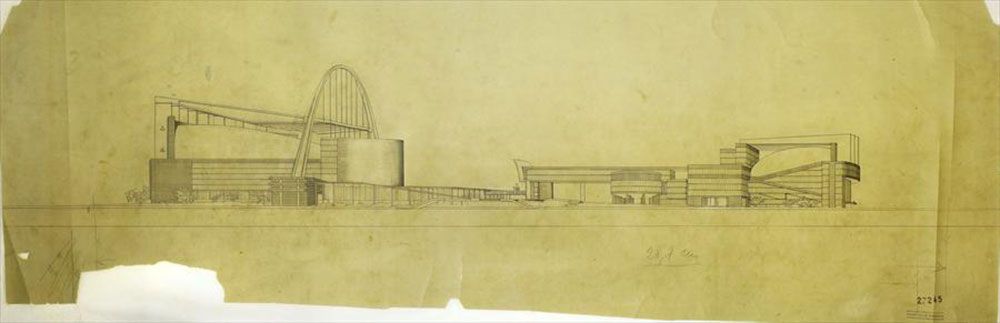

Modern architecture was becoming the basis for the guiding principles of town planning and of the way architecture was conceived, a fact reflected not only in professional articles and on management boards but also in the visible architectural landscape.

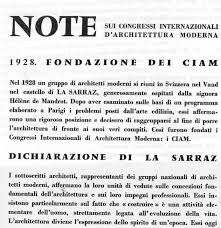

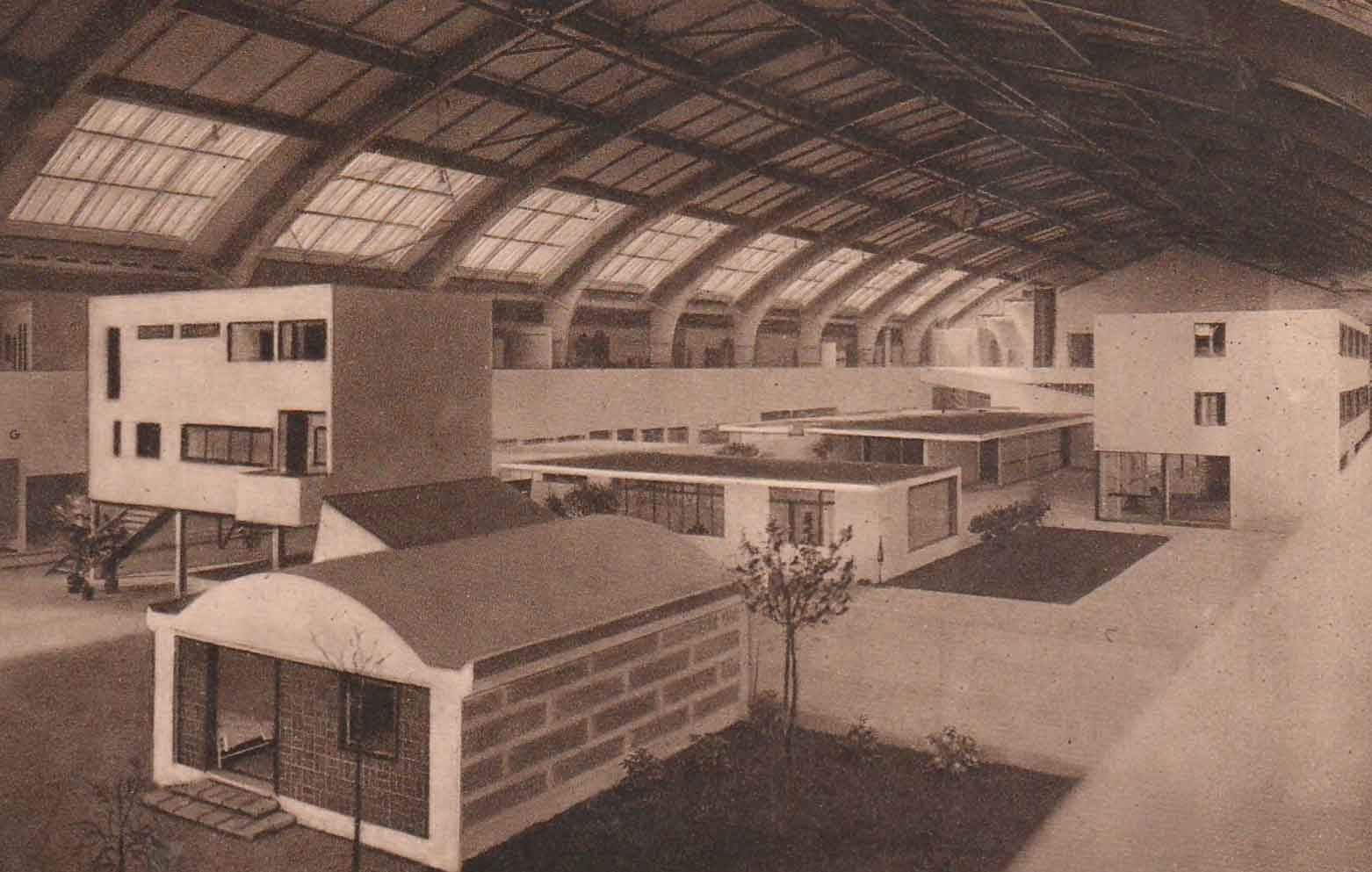

The first International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM) was held at La Sarraz in Switzerland in 1928. It was attended by the most prestigious avant-garde architects who adopted a manifesto, which clearly shows how social, economic, and political considerations were crucial factors in modern architectural theory – a theory that shared many principles with the position subscribed to by Soviet architects of the period.

Architecture must express the spirit of the time that has spawned it. Aware of the deep changes in the structure of society wrought by mechanisation, avant-garde architects recognised that the transformation of the social order and of social life required a corresponding transformation in architecture. The specific aim of the talks at the Congress was precisely to restore architecture to its true economic and sociological basis.

Modern architects in Germany, Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands and Czechoslovakia had already begun to work for a new customer base: people. A small group of French avant-garde architects, including Le Corbusier, hoped that the same would happen in France.

According to the German architect Walter Gropius:

“It is no longer the private villas of the rich that need to be built but hundreds of apartments. Not houses for wealthy capitalists but decent homes that can be used by the working class, homes that do not respond to aesthetic criteria but to objective facts.”

The ideas aired at La Sarraz in 1928 were very close to those expressed by the experts of the time in the Soviet Union. Many architects in the modern European movement publicly voiced their enthusiasm for what was being implemented – or what it appeared was being implemented – in the fields of architecture and town planning in the Soviet Union, but also in the country’s social and political life.

After his first trip to Moscow in 1928, Le Corbusier wrote:

“In Moscow I found people working tirelessly on the invention of a new kind of architecture... on the search for purer, more characteristic solutions... In Moscow one can sense the forthcoming signs – whether artificial or deeply motivated – of a new world.”

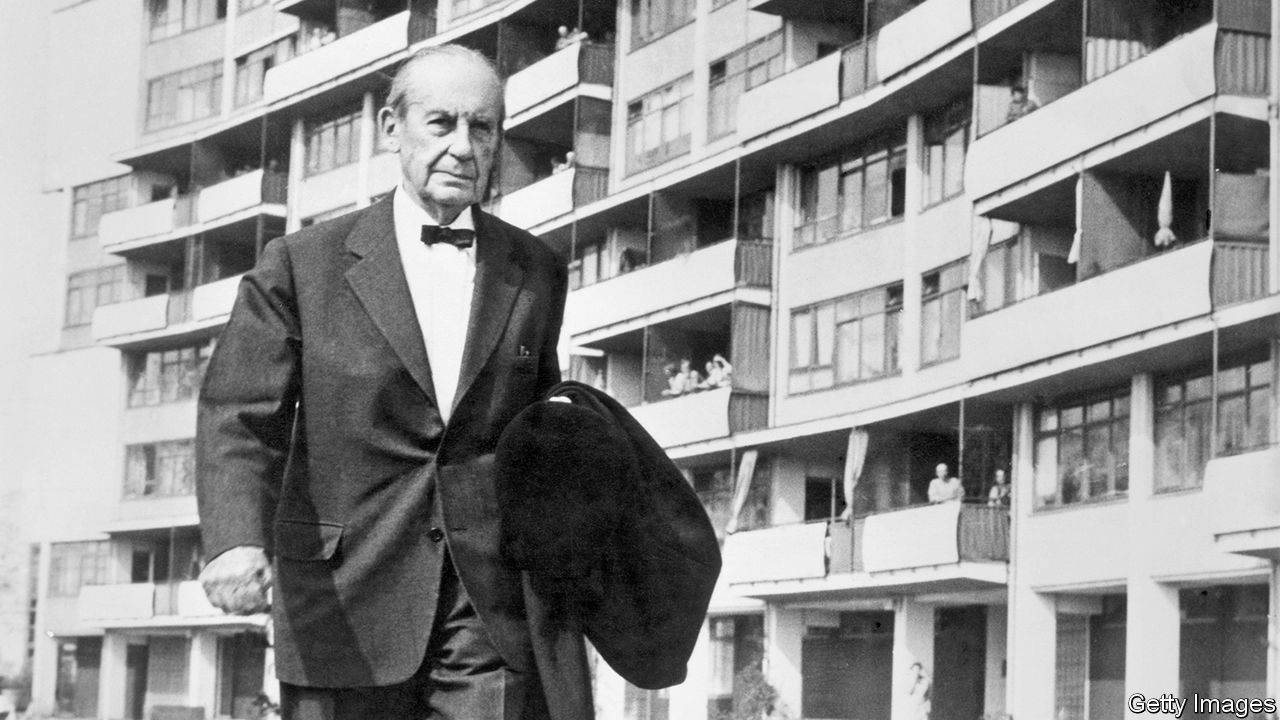

In 1930 Ernst May, the Chief Architect of the city of Frankfurt – and a “bourgeois” architect by Soviet standards – went to work in the Soviet Union with a team of architects and engineers.

Before leaving, he said:

“Politics is none of my business. I am a German architect, and I am working for the Soviet Government in the hope that I can be of use to the German economy at the same time. […] No one can foresee whether the greatest national experiment of all time is going to be successful or not. But for me it is infinitely more important to take part in this immense task than to worry about the safety of my private existence.”

To many architects the West offered only limited projects and the prospect of unemployment.

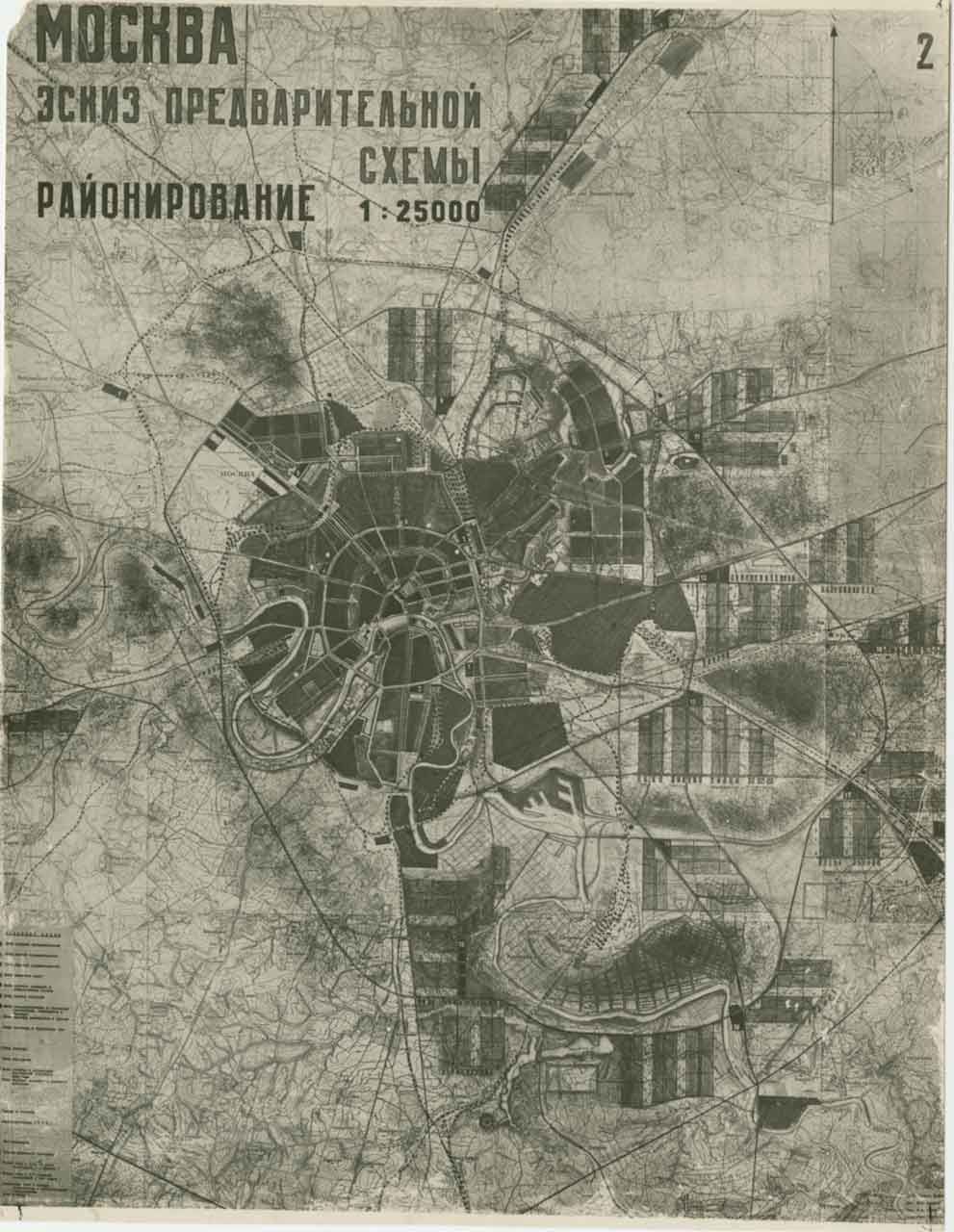

Russia, on the other hand, was seen as the “birthplace” of modern architecture, a country in which scientific planning governed development, unlike the anarchy that appeared to hold sway among Western planners.

The innovative approach to architecture practised in the USSR contrasted with the sterile Western approach based on recourse to historical styles and hackneyed techniques. However, more than anything, change in the USSR was taking place at unprecedented speed.

To many architects the Soviet Union sounded like the land described by Vladimir Mayakovsky in Khrenov’s Story of Kuznetskstroi and Its Builders. In this land, in four years – the four years of the first Five Year Plan (1928-32) – a wilderness must be turned into a garden city.

Comparisons with the West during the Great Depression of the 1930s bolstered this image of the USSR where unemployment was replaced by a labour shortage after the launch of the first Five Year Plan.