THANK YOU

MAESTRO

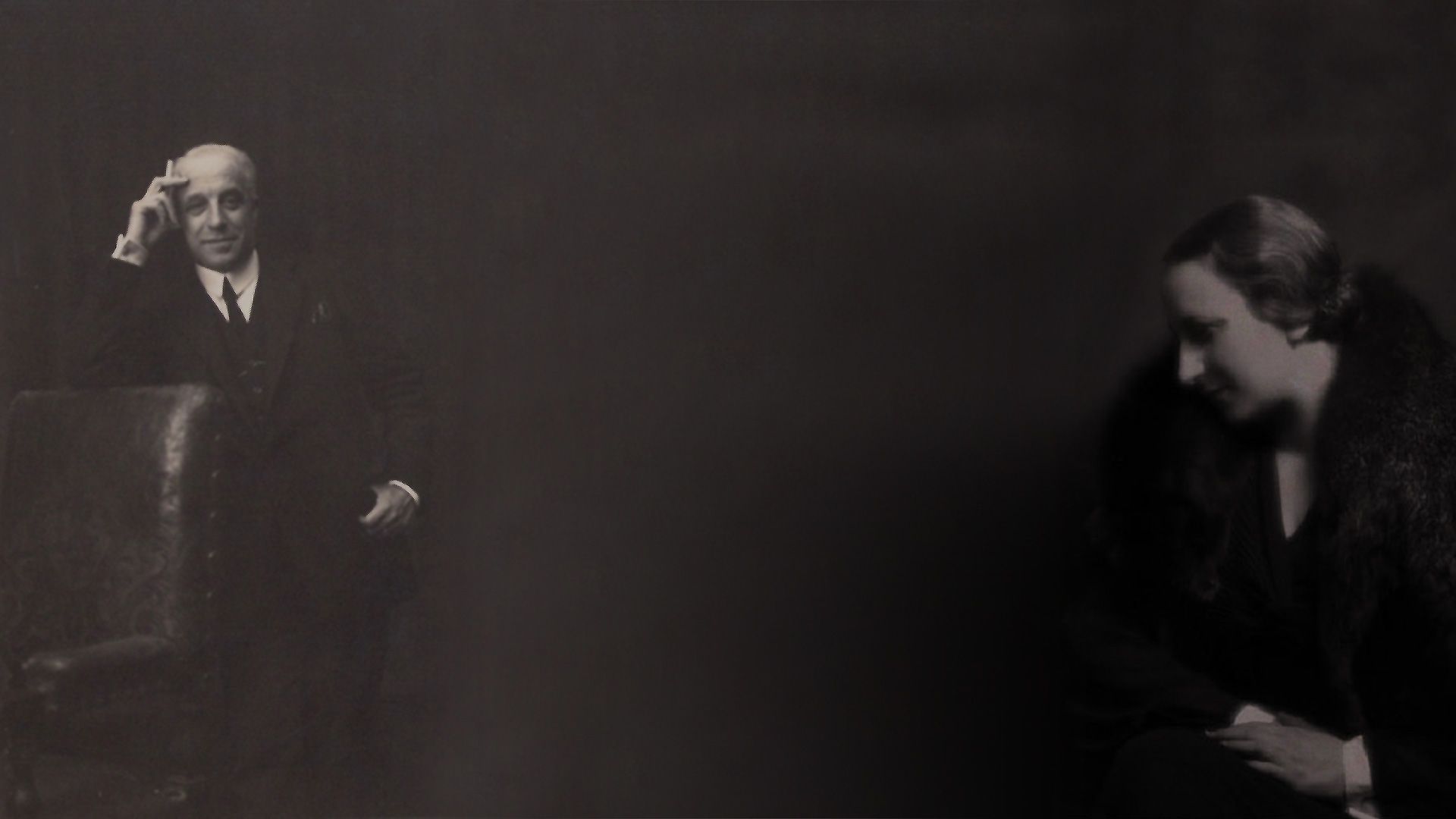

The season of Ettore and Fernanda.

The story of a great mentor and his brilliant pupil, their shared civic and cultural commitment, the war, and reconstruction.

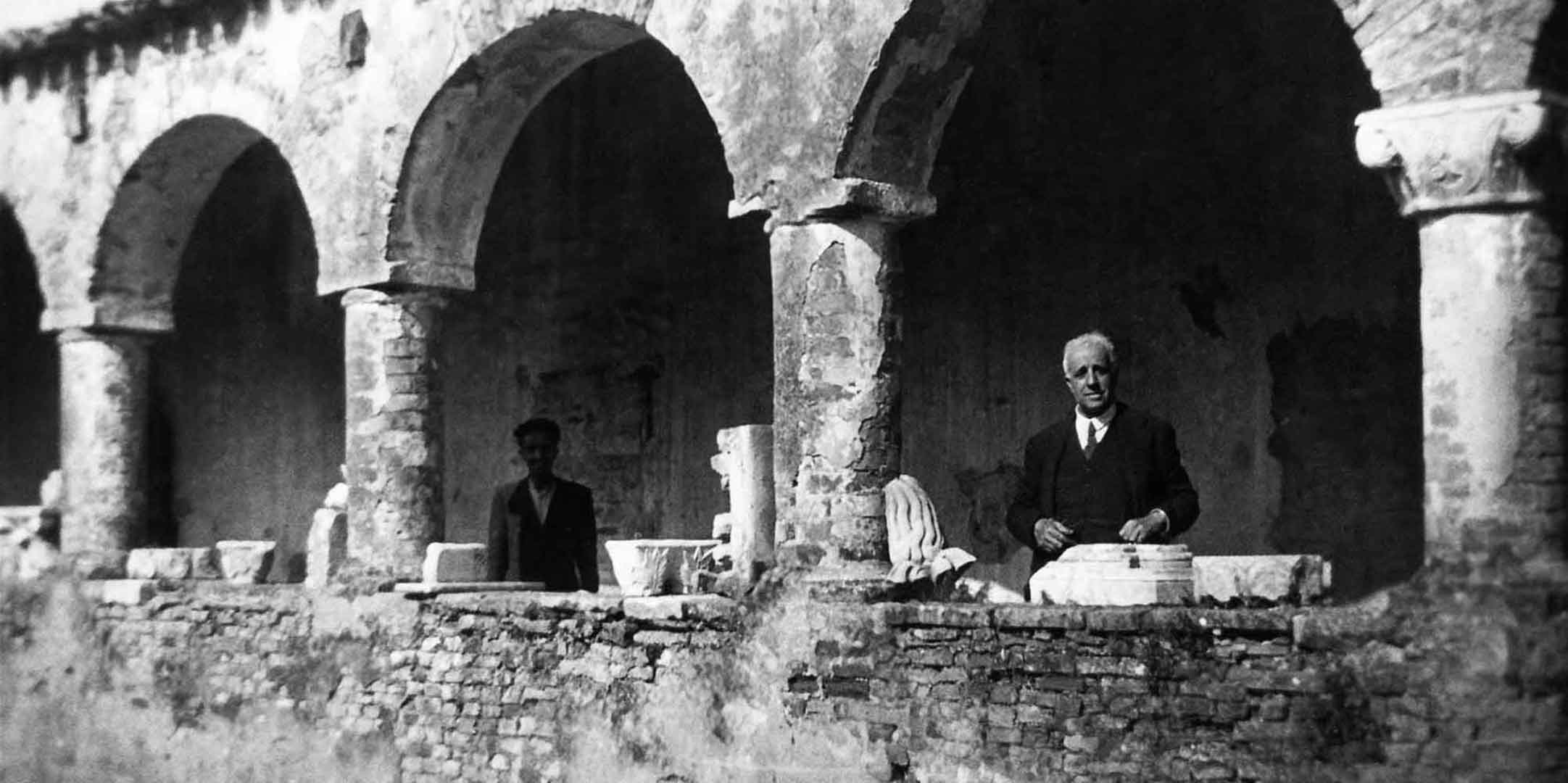

Ettore Modigliani was director of the Pinacoteca di Brera from 1908 to 1935, director general for Lombardy from 1910 to 1935 and the organiser of the most important exhibition of Italian old master works in London in 1930.

He also had the privilege to experience in the first person such rewarding moments in his career as the display of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa at the Brera in 1913, the recovery of works of art stolen from Italy by Austria in 1920, the major overhaul of the Pinacoteca di Brera in 1925 and the foundation of the Friends of Brera Association in 1926.

Italian paintings packed and ready to be shipped to London for the exhibition on 1 January

A young woman aged only 25 appeared on the scene to become his assistant in 1928. Her name was Fernanda Wittgens. They worked together for nineteen years, including on the exhibition in London in 1930.

Modigliani was a talented director and in Fernanda Wittgens he found someone of his own standard, someone who thought like him, who shared his doubts, who solved difficult problems, and who shielded him from the indignation and irritation triggered by others’ small mindedness, offering him the honest criticism that only a true friend can afford to level.

"Nor, on such an occasion as this, can I omit to mention the young lady’s spirit of organisation, a spirit which she displayed to excellent effect when preparing the exhibition of Italian old master works in London in 1930 and during the exhibition itself, to the point where the British Government, on hearing of her work, gave her a decoration which is only on the rarest of occasions conferred on a woman, and a foreigner at that.

In conclusion, I can tell the hon. Committee in all conscience that if a competition were to be held today, not for the post of inspector but for that of director, my consideration and my position on the young lady’s maturity and merit would not change.

Ettore Modigliani

12 April 1933, Letter to the Directorate General for Medieval and Modern Art in Milan

The relationship between Ettore Modigliani and Fernanda Wittgens was one of the most important in Brera’s history.

She was by his side during the search for, and subsequent purchase of, Caravaggio’s masterpiece entitled The Supper at Emmaus now on display in the Pinacoteca di Brera.

“Modigliani is on the scent of a picture; he is chasing a Caravaggio with which the Friends of Brera could cut a very fine figure indeed.

You [know how] difficult and delicate it is, it is best not to talk about it for the time being, especially not to Chierici or Moratti. Once we are sure that it is a Caravaggio and that we can have it, I shall come and explain the situation to you and finalise the plan for getting hold of the painting.”

24 October 1938, Letter from Fernanda Wittgens to Senator Ettore Conti di Verampio, President of the Friends of Brera

Fernanda also offered Modigliani her support during his tough time in exile. Modigliani, who was of Jewish descent, was forced to quit the Brera in 1935. He was transferred to L’Aquila on account of the racial laws exactly a week before he was due to retire.

“1936.

It was at the start of the investigation by the examining magistrate that Minister De Vecchi dealt me the blow of defenestration to L’Aquila. There was no reason to fear that this might influence the magistrate because the magistrature judges based on facts, not gossip, but there was every reason to fear – and seriously too – that Italian grass-roots opinion might associate those charges with my otherwise inexplicable punishment and end up questioning my respectability. That is what truly broke my heart.

[…] Knowing they had Rome’s support, they tried to throw everything at me during the hearing: from the insinuations to the vulgar invective hurled at me by two star lawyers, one of them a ranking Fascist official, and constantly peppered, in an effort to demoralise me, with predictable and scornful cries of “You have been hounded out of Brera! Hounded out of Brera! […], along with “witnesses’ depositions” taken anywhere and everywhere, and by whatever means.

The ranking party official showed no hesitation in bringing into the hearing a few copies of the “Popolo d’Italia” in which I had been violently criticised for anti-Fascism on account of an incident that occurred in Brera one day, or in shouting that, after all, the trial should be considered a political trial.”

from Ettore Modigliani, Le Memorie, 1947

It was at this time that Modigliani wrote Il Mentore, an art history classic which the racial laws prevented him from publishing under his own name, so it was published in 1940 under Fernanda Wittgens’ name.

By the end of 1938 Il Mentore – given that it seemed appropriate to me that the book’s title should instantly declare its aim to provide the first scholarly lessons for finding one’s way about in the topic – was finished and broadly complete in its more than six hundred pages.

But the racial laws broke onto the scene, making it impossible to take any measures with a view to publishing it: no window displays, no reviews, no advertising of any kind, no use of the book for teaching in schools, in short, a complete vacuum around a book printed in all secrecy, thus ensuring that it would fail.

[…] So, what happened?

Well, the situation was patched up by a dear friend of mine and of my family, a heroic art history writer named Dr. Fernanda Wittgens who, tirelessly driven by a desire to ease the fate of a victim of persecution and by a certain sense of gratitude for whatever she may have learnt at my side in her many years as inspector with Brera, offered to conceal my name in the book as others had done before her in similar cases on account of the racial laws.

Heedless of the danger to which she was exposing herself of having to pay for her generosity at the very least with her job at the Brera, or of the fact that she would be barred from ever entering any future competition on account of the impossibility of both presenting and not presenting “Il Mentore” as a title; and heedless of the mental torment she would have to face in potentially earning praise for a work she did not write, she refused to allow me to reject this act of such selfless kindness; I agreed, and the book was published under the name of Wittgens.

Only those who, faced with a favourable opinion, have heard the protests of this noble creature that prompted her in some cases even to spill the beans and reveal the dangerous truth of the matter, only those who have seen her face turn white on seeing a telegram, a letter or the page of a periodical with a favourable review, can judge the torment sparked by her refined sensitivity and triggered by her honest conscience which was unable to tolerate wearing another’s feathers...

To Fernanda Wittgens, a true friend in both favourable and adverse circumstances, my infinite gratitude.

from Ettore Modigliani, Le Memorie, 1947

In 1940 Wittgens entered a competition and won the nomination for the Pinacoteca di Brera, the first woman staffer with the Musei e Gallerie ever to achieve such high office in Italy, carrying on her master’s work while keeping him constantly abreast of events.

… I fight even if I am unable to win, I shall have done my duty. But there are times when nausea suffocates me! Especially when I see the mean-spirited pettiness of men.

Letter from Fernanda Wittgens to Ettore Modigliani, May 1945

And now I am going to share my thoughts with you; and pray do not smile if I spend a little too much time caught up in the clouds of spirituality. There are things one does not like to talk about, but it is sad to think that we might die one day without our dear ones ever knowing what we harboured in our deepest soul.

[…] Mind you, neither the time nor the place are conducive to meditation. People here are chattering as though they were in the drawing room, and we have been here for two hours without feeling any emotion.”

Letter from Fernanda Wittgens to Ettore Modigliani on war and peace, written during an air raid, 1943

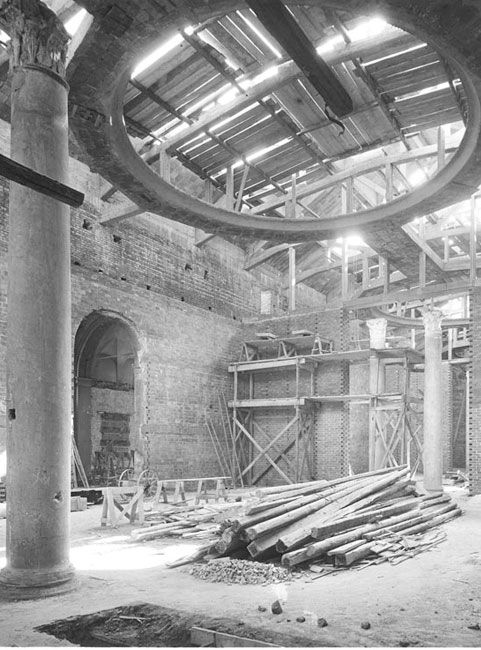

After the war and Modigliani’s return to Milan, Fernanda and he worked together on rebuilding the Pinacoteca di Brera which had been seriously damaged during air raids.

All right, so you mercilessly bomb and burn our most illustrious, historical and monumental cities because, among other reasons, we are not is a position to respond, if indeed we wished to do so. That is the law of war – as people say - and they may be right to some extent, if we accept the motive of so-called military targets.

[…] Who is unaware of the bitterness still festering in Venice after 28 years over Austria’s destruction of the miraculous Tiepolo ceiling in the Scalzi, a disaster still branded an act of abominable barbarity even today? The Scalzi was a stone’s throw from the railway station, but the Filarmonica, Santa Chiara, La Scala hit by incendiary bombs, or Brera, Sant’Ambrogio, the Palazzo Reale Normanno and San Simpliciano and a hundred other marvellous Italian palazzi? No, not that, a thousand times no.”

E.M., Il Giornale 12-08-1943

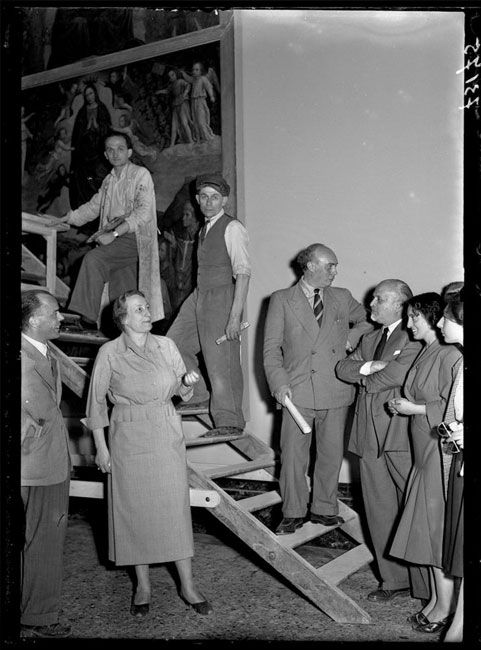

Together they managed to reopen the Small Brera with seven restored rooms in 1946 and they devoted their energies to the restoration of Leonardo da Vinci’s Cenacolo – it, too, badly damaged during the war.

Dear Director Brandi,

Forgive me if in writing to you I am ignoring the prerogatives of hierarchy and adopting a tone of simple human truth. I would hate you to think that there is a clash between Modigliani’s ambition and the ambition of Pacchioni.

Modigliani has never been driven by ambition but by the lofty sense of responsibility which has informed his entire life and work, and which has prompted him to plead with the Ministry to restore the Cenacolo without delay, to avail itself of concrete experience without idolising fanciful attempts to expose the relic in the meantime to trials which, thank God, were not but could so easily have been lethal…

Modigliani’s is not ambition, it is passion, pure passion.

Modigliani is now distant from these affairs. He is slowly dying; it is a matter of days, maybe hours. He would smile at this letter of mine. But I felt it my duty to make this final gesture of loyalty towards the man who for years has been my master and who will always remain an example for us. Forgive my boldness.

18 June 1947, Letter from Fernanda Wittgens to Cesare Brandi

Ettore Modigliani died on 22 June 1947, four days after this letter was written.

It was Fernanda Wittgens who reopened the Museo Teatrale alla Scala which Modigliani had created decades earlier and which had been closed during the war. And it was she, again, who finally opened the Great Brera in Modigliani’s name on 9 June 1950, with all thirty-eight rooms completely restored with new layouts designed by Pietro Portaluppi.

“By contrast, these peaceful rooms, in welcoming the treasure of the Napoleonic collection of Venetian and Lombard painting intact, can give you an idea of the horror of war and of the spiritual victory of rebirth. A different voice should have declaimed this miracle, the energetic voice of the man who first devised it, Ettore Modigliani.

9 June 1950, Fernanda Wittgens, speech at the official opening of the Pinacoteca

Special thanks to the Pontremoli family and to Marco Carminati.

From Le Memorie by Ettore Modigliani, Biblioteca dell’Arte, Skira